News

BTI Says Goodbye to Klaus Apel

Klaus Apel, former professor at BTI and Professor emeritus at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. (Photo by Sheryl Sinkow)

Professor Klaus Apel can pinpoint the exact time he chose to be a plant scientist.

As a young person, Apel was seriously interested in birding and so he entered the University of Hamburg to study biology, with a special emphasis on zoology. But in a year-long, required course, he encountered the “Medulla Frog” lab.

“You’d get a living frog and you have to cut off its head. Then you have the remaining frog and you see, without its brain, what the frog is still capable of doing,” said Apel. Using acetic acid and a paintbrush, he had to touch different parts of the frog’s remaining body to see which muscle movements remained. “I was so disgusted; I was almost unable to do the experiment. On the spot I decided, no, this is not what I wanted to do for the rest of my life.”

It was then that he decided that plant science would be his intended career. He transferred to the University of Freiburg, where a famous and dynamic young plant science professor named Hans Mohr taught. During his training, Apel was required to give a seminar, which made him incredibly apprehensive. He persevered, however, giving an exemplary talk on the Golgi apparatus. Mohr had attended and congratulated him on the excellent seminar.

“From that time on, I had gained the self-confidence that I could make it,” said Apel. “Even later as a professor, that experience helped me to handle and support students who didn’t feel confident enough.”

Apel can likely thank Mohr, and to a lesser degree, the medulla frog, for setting him on a trajectory that would lead to a highly successful career in plant science. At the end of September, Apel retired from the Boyce Thompson Institute, ending a career that spanned more than five decades. During this time, he investigated how genes in the nucleus control proteins in the chloroplast, the function of plant pigments called phytochromes and finally, the role of reactive oxygen compounds in plants’ response to stress. His lab was the first to show that a high energy form of oxygen, called singlet oxygen, was not necessarily toxic to the cell, and served an important role in cell signaling. While Apel will close his lab at BTI, his former lab members will continue using the experimental system that they developed to study singlet oxygen signaling.

A Prussian education

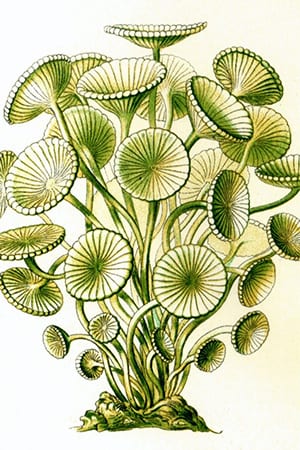

Apel graduated from Freiburg in 1967 with a staatsexamen, the German equivalent of a master’s degree. During his time there, Apel heard a talk from a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Cell Biology in Wilhelmshaven, who was investigating a single-celled algae called Acetabularia. These unique algae could grow to be 10 centimeters long, with a single nucleus located in the base, a long stalk and a cap at the top. The work interested him enough that he started a Ph.D. program at the institute in the lab of Hans-Georg Schweiger to study these algae.

A drawing of Acetabularia mediterranea by Ernst Haeckel.

“I could show that some of the chloroplast proteins actually were under the influence of nuclear DNA, which was rather novel at that time,” said Apel.At the time, scientists had only recently demonstrated that DNA was the carrier for genetic information in cells and there were some who thought that chloroplasts could function independently because they had their own set of DNA. Acetabularia species provided an opportunity to explore how DNA in the nucleus regulated cellular growth and the function of chloroplast proteins by swapping the nuclei between different species of the algae.

He graduated with his doctorate in 1970, but stayed on for two years at the Max Planck Institute as a research assistant, which included six months of travel all over the South Pacific to collect new species of Acetabularia. He visited the Philippines, Papua New Guinea and Taiwan, saw rusty remnants of warships from World War II on the Solomon Islands, and observed people living in huts with thatched roofs, who traveled by canoe. He said it was an amazing experience to visit these pristine locales before they became tourist destinations.

Apel left the institute in 1972 to take his first position in the United States. He completed a NATO postdoctoral fellowship and then a German Research Foundation Fellowship at Harvard University in the lab of Lawrence Bogorad, a pioneer of photosynthesis research, who is noted for his work in chloroplast biology. In Bogorad’s lab, Apel had immense independence and the autonomy to explore his own interests, on his own schedule. He realized that “once you have the freedom of doing something for yourself, rather than following orders, you become much more productive.”

He also realized what a “Prussian” experience he had had at the Max Planck Institute. In Germany, at the time, labs were extremely hierarchical. He had arrived at the lab by 8 am each day so that his boss could walk the halls and see that all were accounted for. But at 8 am on his first day in the Bogorad lab, he was the only one there. A secretary finally arrived at 8:30 to make coffee, who advised him to start coming in later.

Apel would have stayed longer in the U.S., but visa issues sent him back to Germany where his old professor, Mohr offered him a position in his department at the University of Freiburg. There, he studied phytochromes using new molecular biology techniques. Though he had a permanent position in the department, the opportunity to be a full professor arose in 1982, and Apel joined the University of Kiel as the Chair of Botany.

The “one-eyed among the blind”

As the new head of the department and the Kiel Botanical Garden, Apel was assigned a secretary, as befitted his position.

“I had never had a secretary, so I was asking myself, ‘What am I going to do with a secretary?’” said Apel. “This takes away a lot of my time just making sure the secretary has something to do.”

The associate professors below him in the hierarchy, many of whom were much older, realized that Apel was an inexperienced manager, and began giving his secretary additional tasks to do. As his administrative duties piled up and he transferred more and more to his secretary, she was totally overwhelmed. Eventually, Apel was forced to reclaim his assistant.

In his eight years at Kiel, Apel used molecular biology techniques to answer diverse questions on topics such as the timing of flowering, the biology of mistletoe, toxic proteins in seeds, and senescence. As the only person using these new technologies in his department, he felt like a “one-eyed person among the blind.” Being on the cutting edge of molecular biology helped him to attract a large number of students. Whenever an undergraduate project took off, the young researcher would continue on as a graduate student. In this way, Apel’s lab grew and spread to take over unclaimed space in the department.

But despite his lab’s successes, Apel found it challenging to master and adopt new techniques with a lab composed primarily of students. He decided to sharpen his skills by returning to the U.S. to spend a year in the lab of Christopher Sommerville at Michigan State University. Sommerville was one of the major early proponents of Arabidopsis as a model plant, and Apel learned to use the species to screen and identify mutants so that he could answer questions using molecular genetics. He was surrounded by highly motivated, intelligent people, which left him feeling like a one-eyed person among the two-eyed.

A first retirement and second career

Next, Apel assumed a professorship at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETH), where he used Arabidopsis mutants to study chlorophyll synthesis. While screening for interesting mutants, he found a plant that releases a burst of singlet oxygen when it goes from darkness into bright light. These mutants enabled him to investigate the role of singlet oxygen in stress responses in plants, and their importance in signaling. He discovered that it was not the singlet oxygen that killed off cells in the plant, but rather the signaling pathway that was triggered when the plant detected the oxygen compounds.

He pursued research on singlet oxygen signaling pathways at ETH until he came up against the mandatory retirement age of 65 in Europe. With questions still left to answer, he began looking for research positions in the U.S. where he could continue to do his work. BTI’s president, David Stern, happened to be in attendance at his retirement party at ETH, and they discussed the possibility of Apel coming to BTI.

Apel enjoyed birding along Cayuga lake.

“Klaus had both a very exciting scientific idea that he wished to pursue at BTI, and long experience in scientific mentoring and administration,” said Stern. “His work had themes very much in keeping with BTI’s scientific persona.”

After consulting with colleagues at several universities and institutions, he decided on BTI and established a new lab at the institute. He was grateful for the opportunity to continue his work, however, he found it difficult to adjust to the U.S. system for funding research. In Europe, a faculty position comes with guaranteed research funding and salaries for lab members. This system gives scientists maximum flexibility to pursue their interests. But in the U.S., scientists must tailor their questions to the whims of funding agencies and face steep competition for grants. With so many high quality applications being turned down, to Apel, the process began to feel like a lottery.

Between start-up funds and two successful grant applications, one from the National Science Foundation and one from the National Institutes of Health, Apel was able to support a small, yet efficient, lab throughout his eight years at BTI. He is leaving on a high note—his group’s most recent work appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Apel will return to Europe where he and his wife keep an apartment in Zurich and a house in Germany. He will continue to serve as a professor emeritus at ETH. His former postdoctoral scientist Liangsheng Wang plans to continue the work on singlet oxygen signaling and will be close enough for Apel to visit. Wang spent almost four years at BTI, leaving this past August to work as a scientific assistant at the Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich.

“It was a great pleasure to work with Klaus Apel,” said Wang. “He and his coworkers explored a new research area that is of great importance.”

In their work together, they discovered that different pathways function in mature and young leaves to trigger cell death in response to singlet oxygen. While they identified the protein that controls the response in young leaves in their recent paper, the pathway in mature leaves is still unknown.

While there will always be new questions to ask, Apel is pleased that he has come to a good stopping place in the course of his research.

“The most challenging and satisfying work has been the development of the experimental system that we used to analyze the singlet oxygen, which I have been doing here [at BTI],” said Apel. “The part that I was mainly interesting in, I could finish in a way that we found very satisfying. So that’s why I think this is just the ideal point to stop.”