BTI summer intern Emily Humphreys poses with plant in the genus Allionia, also known as Trailing Four O’clock.

On March 3, I thought I knew what my summer would be like. I had just been accepted into BTI’s summer Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) program. I imagined myself in a greenhouse surrounded by vegetation and scribbling in a lab notebook. I imagined attending talks in towering lecture halls and spending hours sitting at a computer squinting at genetic sequences.

Unfortunately, over the next few weeks, the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic came into full light. I received an email at the end of March informing me that the REU program would be canceled. It was not unexpected and was certainly the right decision, but still I felt a twinge of disappointment as I let go of a hope I hadn’t realized I’d been holding on to. What I did not know was that the staff at BTI were beginning to imagine something new.

In the following months, they built a virtual program from the ground up. With input from students, they designed the Undergraduate Professional Development Series, a summer-long program full of lectures from scientists, opportunities to talk with researchers, and spaces to get to know more than 100 other undergrads interested in plant science. My aim for this blog is to catalog my experience participating in the program and give you a glimpse into what I’m learning.

After joining the program, our first task was to post an introduction in the online classroom. People wrote about their research interests, favorite plants, hobbies, and sometimes even pets. It was great to be able to scroll through and get a sense of the people with whom I’m sharing this online community. There were dozens of posts, and Delanie Sickler, the Education and Outreach Director at BTI, responded to each of them, even if it was just to say, “It’s great to meet you!”

A few days later, we attended our first scientific discussion. BTI’s Dr. Georg Jander presented a talk called, “Biosynthesis of cardiac glycosides, plant metabolites that either kill you or make you stronger.” It’s a pretty excellent title. He described his research working to understand the pathways that underlie the synthesis of cardiac glycosides. These plant-made molecules serve as a defense against hungry herbivores and can be very toxic to all sorts of animals including humans. When carefully prescribed though, cardiac glycosides can be therapies that help regulate heart rhythm. What really stood out to me from his talk was how his team breaks their research question down into small components. Each experiment builds upon the previous experiments and gets the researchers just a little closer to understanding how cardiac glycosides are made.

Since then, there have been many more online meetings. Paul Thomas, a library associate at the University of Kansas and past Wikipedia Visiting Scholar with WikiEdu, explained the process of editing Wikipedia and how the site works to make science more accessible to the public. That night I added the first citation to the Wikipedia page for the genus Allionia. Also known as Trailing Four O’clock, these fascinating little plants have inflorescences with three flowers that masquerade as a single bloom.

A few days later, all of the undergrads had an opportunity to get to know each other better. We split into zoom breakout rooms and talked about everything from the weather in Florida to the virtues of oboe music. A few day later, we got the chance to talk with graduate students and postdocs from Cornell and BTI about what their lives as researchers are like and how they got to where they are.

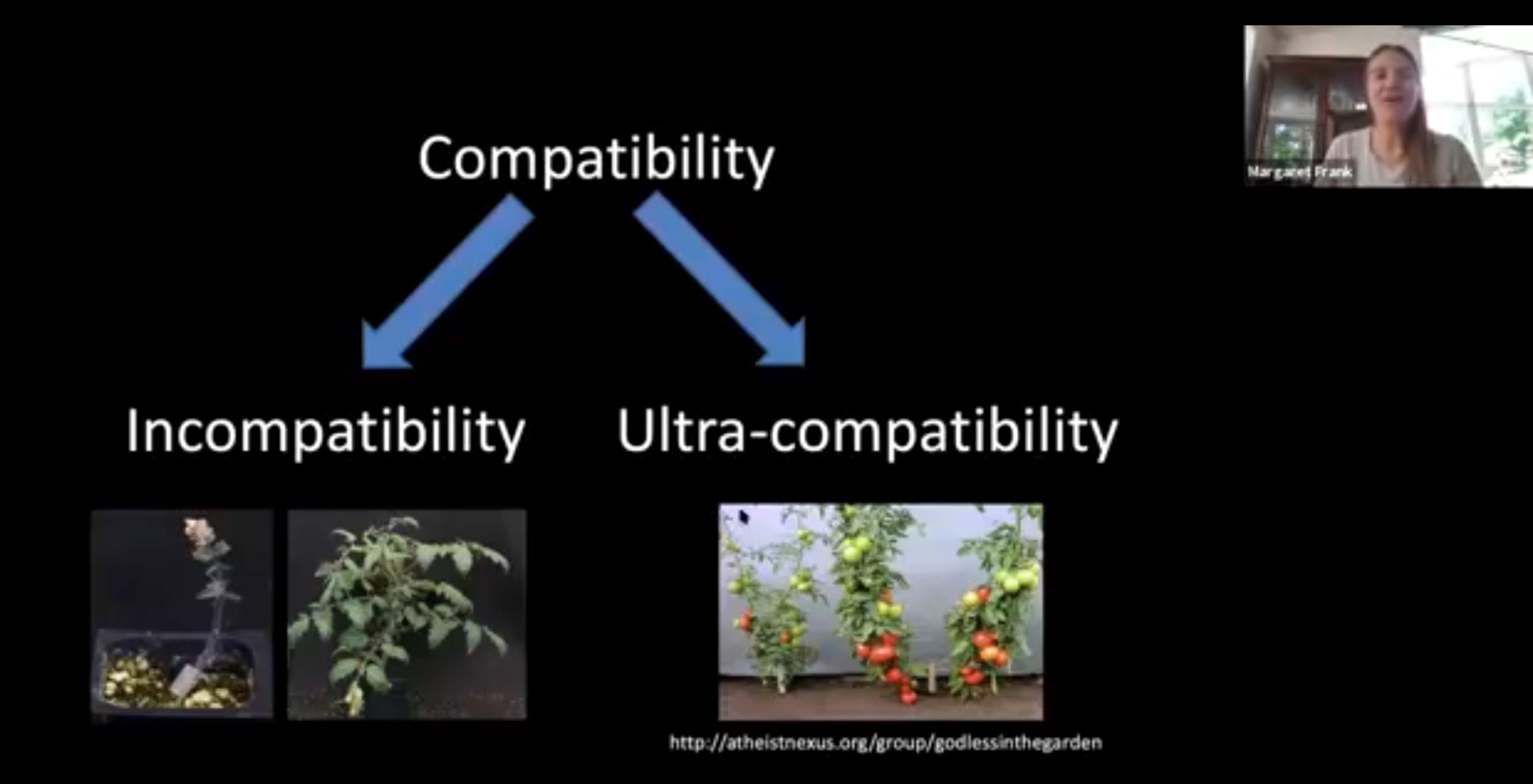

One talk from the last two weeks has stuck with me the most. On Wednesday, Dr. Margaret Frank from Cornell University presented her work on grafting tomatoes, taking the root of one plant and encouraging it to grow together with the shoot and leaves of another. The grafting process is an incredible disruption: the connections the plant relies on, the ones that carry water, nutrients, and chemical messages, are severed. Sometimes the process fails and the new plant dies. However, with care and attention, more often than not the graft succeeds. As the plant heals, new connections form. Sometimes a graft between two different species can be even more successful than either of the two plants would be alone.

Her work to understand why this might be the case is captivating from an academic standpoint, but thinking back on the summer so far, I have found it resonant in a different way. It seems absurd to me that two plants cut in half and stuck together could survive, but often they do. They continue to live and grow despite all the odds. In a similar way, the shift to virtual life these past few months has been an incredible disruption, yet even so, people have found ways to form new connections and continue to grow despite it all. So, this summer I am hoping to be like a grafted tomato, forming new connections and continuing to grow together with those around me no matter the circumstances.