News

Professor Dan Klessig retires after 48 years of research

Former Boyce Thompson Institute president Dan Klessig, shown here at his desk in 2015, is stepping down from research after 48 years, leaving a legacy as a passionate scientist, an innovative leader and an inspiring mentor. Image credit: Boyce Thompson Institute.

After 48 years of performing molecular biology research, including 22 years at Boyce Thompson Institute, Professor Dan Klessig retired on December 31. The former BTI President will remain associated with the Institute as an Emeritus Professor.

A self-described “farmer from Wisconsin who raised pigs to put himself through college,” Dan discovered molecular biology as an undergraduate student in biochemistry at the University of Wisconsin during a lecture by Robert DeMar. “I knew then that molecular biology was what I wanted to do for the rest of my life,” he says.

His colleagues and former lab members remember Dan as a hardworking scientist, forward-thinking leader and generous mentor.

Passionate Scientist

Following completion of a Master’s Degree in molecular biology as a Marshall Scholar at the University of Edinburgh in 1973, Dan made his first significant scientific breakthrough as James Watson’s last graduate student at Harvard University and Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL).

It was here that Dan performed foundational research that led to the discovery of split genes and RNA splicing in human adenoviruses (e.g., this 1977 paper in Cell and this 1980 paper in Journal of Molecular Biology), which eventually won the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for his CSHL colleague Richard Roberts and Phillip Sharp of MIT.

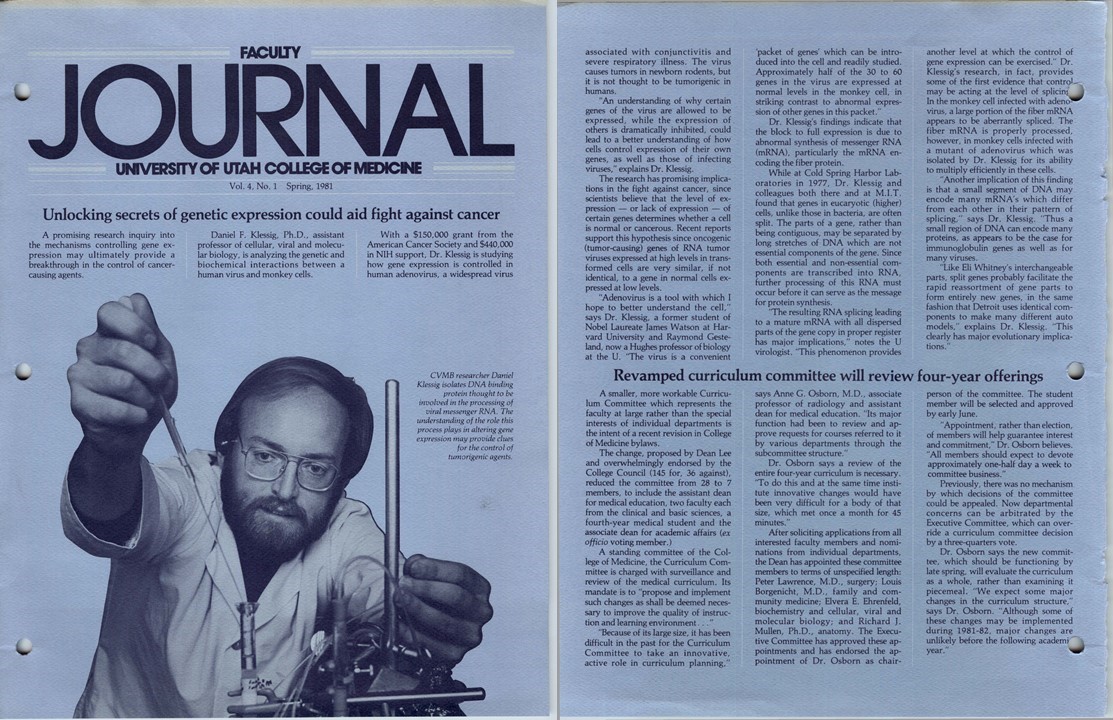

Dan continued studying adenoviruses at University of Utah from 1980 -1985, while expanding his research to plants.

“Growing up on a farm, I had an affinity for plants. In addition, I spent countless hours with Barbara McClintock at CSHL, who encouraged me to study plants,” Klessig recalls. “Importantly, she was one of the few who encouraged me to follow my instincts, when many of my colleagues, including Watson, believed Roberts and I were studying an artifact.”

“There were several critical pieces to the RNA splicing puzzle; if I hadn’t done my piece then someone else would have, probably within months,” Klessig says. “I wanted to make real contributions to fundamental discoveries that might be delayed years, perhaps even decades, rather than months without my participation. Molecular biology was still a young field at the time, especially in plants, and I felt I might be able to make a real difference there.”

Dan made his next big scientific breakthrough at the Waksman Institute at Rutgers University, where he was a professor and Associate Director from 1985 to 2000.

In 1990, Dan’s research group, together with colleague Ilya Raskin, discovered that salicylic acid is a key plant hormone that regulates immune responses (e.g., this 1990 paper in Science and this 1991 paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences).

“Dan’s research on salicylic acid has contributed enormously to our understanding of how this important hormone moves within plant tissues, binds to specific proteins and impacts the plant immune system,” says Greg Martin, a plant molecular biologist and the Boyce Schulz Downey Professor at BTI.

“These insights lay the foundation for the development of crop plants that can be grown with fewer pesticides, which will be better for the environment and for human health,” Martin adds.

The salicylic acid discovery drove Dan’s research for the next 30 years, including once he joined BTI as a professor and President in 2000.

His team revealed the multiple molecular mechanisms of action of salicylic acid and its derivatives in combating disease in both plants and humans (e.g., this 2015 paper in Molecular Medicine, this 2016 paper in Frontiers in Immunology, and this 2019 paper in Scientific Reports).

Dan’s research at the University of Utah made the cover of the Spring 1981 issue of the university’s Faculty Journal. Image credit: Spencer S. Eccles Health Sciences Library, University of Utah.

“Salicylic acid has many potential health benefits in humans; one could even argue that it is the active ingredient of aspirin,” Klessig says.

In 2013, a chance encounter with chemist and professor Frank Schroeder at the communal BTI coffee pot led to Dan’s latest significant contribution to science. The pair found that chemicals excreted by nematodes – tiny worms that live in the soil – induce plant immune responses that enhance resistance against pathogens and pests (e.g., this 2015 paper in Nature Communications and this 2020 paper in Nature Communications).

This research led to the creation of a startup company, Ascribe Bioscience, in 2017. Klessig plans to remain involved with Ascribe as a scientific advisor.

“Dan is genuinely enthusiastic about science and is always interested in hearing about new ideas and hypotheses,” says Schroeder. “He has been invaluable as a sounding board and mentor.”

Innovative Leader

While science has always been Dan’s passion, he also successfully tackled administrative leadership, helping to revitalize two research institutes: the Waksman Institute and BTI.

“In my 15 years at the Waksman Institute, Director Jo Messing and I, as Associate Director, spearheaded the development of two new institutes – the Center for Advanced Biotechnology and Medicine, and the Biotechnology Center for Agriculture and Environment – and helped to hire more the 150 new faculty members in the biological sciences across Rutgers, including five Howard Hughes Investigators,” says Klessig.

“I’m proud to have contributed to the revitalization of the Waksman Institute and help build Rutgers into a first-class research university, because it had a much broader impact than just my own research,” he adds.

Klessig performed a similar revitalization at BTI during his four years as president (2000-2004).

David Stern, BTI’s current president, explains that before Dan’s tenure, BTI’s research structure consisted of a handful of departments, like Plant Molecular Genetics and Forest Biology.

“The faculty felt the department structure was inhibiting research, so Dan got rid of them and encouraged researchers to collaborate across disciplines,” Stern says. “We see this type of collaboration as common sense now, but it was very forward-thinking at the time.”

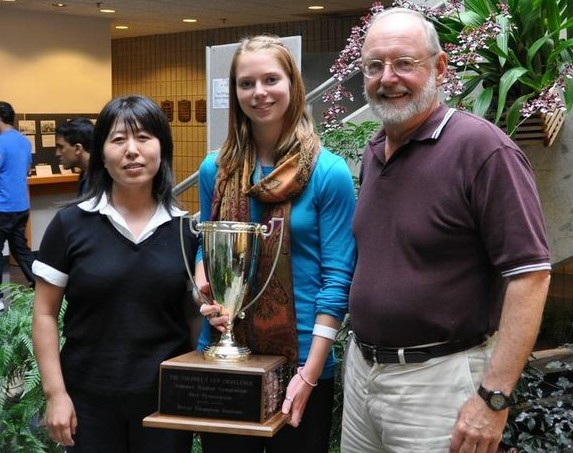

Dan Klessig poses in the BTI atrium with postdoc Miaoying Tian (left) and undergrad intern Sarah Jenson (center), who won the Colonel’s Cup for best oral presentation in 2013. Image credit: Miaoying Tian/provided.

Other steps Klessig took to encourage collaborative science included the reconstruction of laboratory space, and establishing more shared equipment. “We renovated about 60% of the labs to make them physically larger,” he says. “It is much easier to succeed in science with large groups of people working together.”

To encourage research competitiveness and excellence, he initiated 9-month rather than 12-month faculty appointments, and instituted pay-for-performance and a post-tenure system with real consequence. The latter two are based on annual review of faculty performance, with input from faculty peers.

Klessig and two Cornell professors, Tom Eisner and Jerrold Meinwald, initiated the BTI–Cornell University Molecular and Chemical Ecology (MACE) program, under which Maria Harrison, Georg Jander and eventually Schroeder were recruited to BTI.

“Dan is a fantastic scientist, and BTI owes him so much,” says Schroeder. “As president, he wanted to bring in faculty who would be internationally recognized as at the top of their fields. Dan saw the value of integrating chemistry, and his investment in chemical ecology really helped shape the Institute as it is today.”

Inspiring Mentor

Throughout Dan’s career, he has mentored 82 postgrads from 18 countries representing every continent except Antarctica. As Stern says, “Dan’s scientific legacy continues at institutions and companies around the world.”

One of these postgrads is Hong-Gu Kang, now an Associate Professor Biology at Texas State University. Kang spent 11 years in Dan’s lab at BTI studying the genetic components involved in plant immunity.

“Dan was a great boss. If I were able to go back in time and do my first postdoc over again 100 times, then I would choose Dan every time,” he says. “What I most learned from him was how to love science and how to approach science by asking questions from every possible angle. That approach is still flowing through my lab.”

Kang adds that the three main descriptors he would use for Dan is that he worked really hard, loved science and was highly organized. “I’ve been trying to copy those characteristics, but am only at maybe 50% of Dan’s efforts – nowhere near 100%.”

Miaoying Tian, currently an associate professor at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, is another of Dan’s former postdocs who says he taught her how to be an independent scientist.

“During my PhD, I worked very closely with my advisor,” Tian says. “But when I started my postdoc with Dan, I learned that I needed to make plans by myself. He would ask, ‘What do you want to do? Why do you want to continue?’ I started to follow that advice, so whenever I met with him I was prepared. That really helped me learn to be independent.”

Tian, who worked with Dan at BTI for 5+ years searching for binding proteins of salicylic acid in plants and humans, also cited the way he ran lab meetings as helping her prepare to become a professor.

“Every week, one person would report their work, and another person would report on 10 to 15 recent publications in their field,” Tian says. “We were exposed to so many new articles, I really expanded my knowledge and felt comfortable when applying for professorships.”

“Dan really trained the postdocs and prepared us to be professors, and he was very supportive when we looked for jobs,” Tian says. “Many of Dan’s postdocs went on to become independent primary investigators.”

Uwe Conrath also credits his time in Dan’s lab with helping him become a professor.

“My scientific output as a postdoc with Dan was great, with four publications in less than two years, two of which were in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,” says Conrath, now a Professor of Plant Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at RWTH Aachen University in Germany.

In the Klessig lab at Waksman Institute in the early 1990’s, Conrath studied the modes of action of salicylic acid during the induction of plant disease resistance, including the roles of catalase and protein phosphorylation.

Pradeep Kachroo worked with Dan for five years, transitioning with him from the Waksman Institute to BTI, studying Turnip Crinkle Virus and genetic suppressors of salicylic acid-insensitive Arabidopsis.

“Dan gave us complete independence to execute our thoughts, and we could take up any number of projects and explore just about any aspect,” says Kachroo, now a Professor of Plant Pathology at the University of Kentucky.

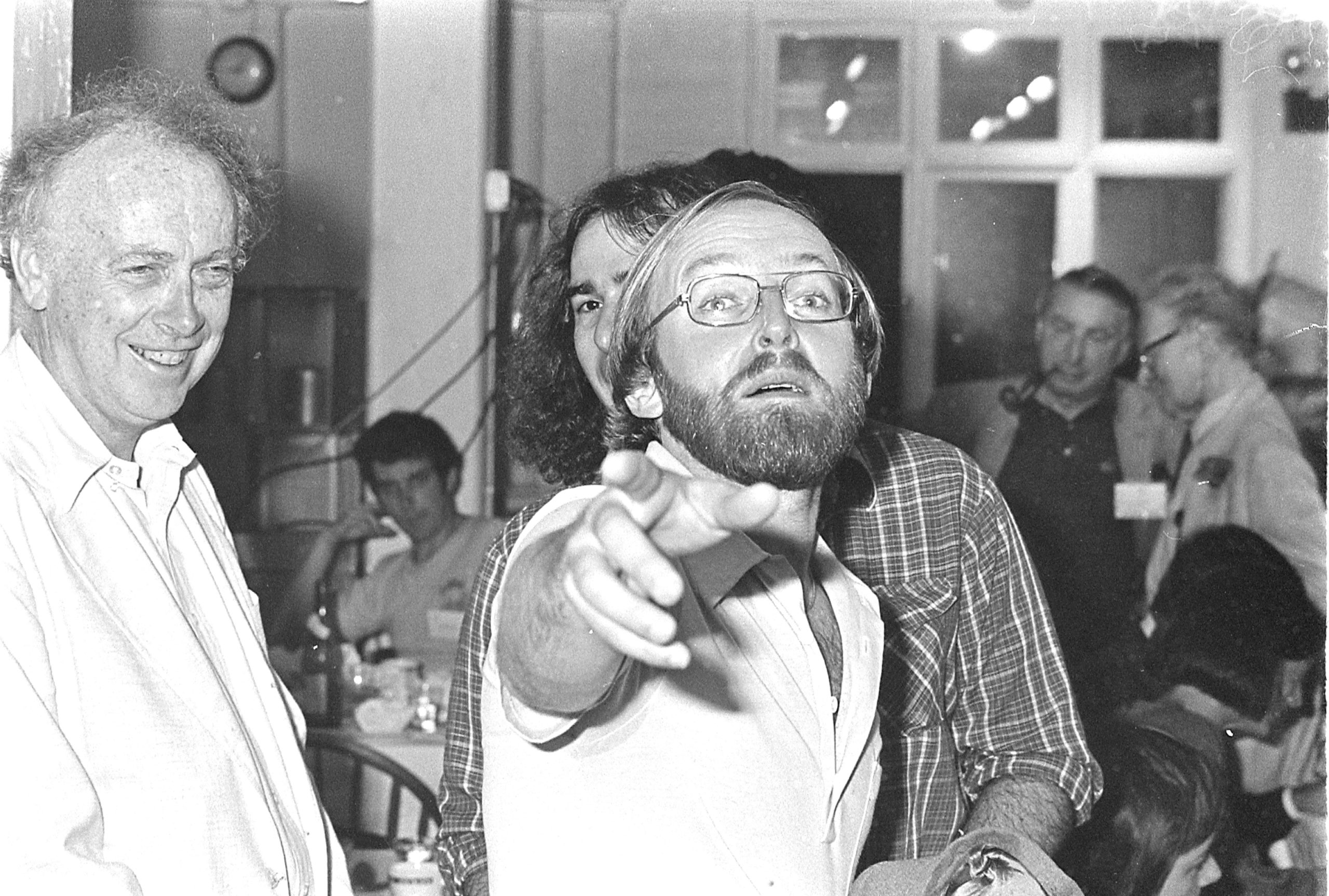

Who’s that? Dan Klessig in 1979, at a Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory symposium, with his PhD advisor James Watson looking on. Image credit: Courtesy of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Archives.

John Carr, now a Professor of Virology at University of Cambridge and Vice President of Corpus Christi College in the UK, echoes that Dan encouraged his postdocs to pursue independent projects.

“I joined Dan’s lab to work on light-regulated gene expression in plants,” he says. “However, with Dan’s encouragement I also continued my previous work on plant–virus interactions, which led to the discovery that salicylic acid is an important defense signal.”

Carr was a postdoc with Dan for five years in the 1980’s, moving with him from the University of Utah to Waksman Institute.

Kachroo and others say that Dan’s work ethic is unrivaled. “Dan was always the first one in the lab, and he stayed longer than most,” says Kachroo. “He often started his work day at 4 am. I was able to match his start time only once, and that was because I had an early morning flight to catch.”

Dan’s former lab members also remember with fondness how he would help them outside of the lab.

“Dan helped his people anyway that he could, from hauling furniture for their apartments to helping with their groceries,” Kachroo recalls.

“And at least once a year he would invite the lab to his home, and open up his bar to everyone,” Kachroo adds. “He had a great collection of all kinds of liquor, and we always looked forward to emptying his collection, but we could never manage to do it.”

Kang says, “Dan was always really good to the kids and family members of his lab members. He had high expectations and could be really tough in the lab, but outside of the lab he was really nice and helped take care of our families. My kids are now adults and still talk about their fond memories with him.”

Conrath recalls that when he and his young family moved to the U.S., Dan and his wife gave them a very warm welcome.

“Soon after we arrived, Dan and Judy went on their honeymoon and left us their home, car, everything – just to make us feel as comfortable as possible,” says Conrath. “He asked only one thing from me: I had to cut the lawn at least once a week.”

What’s Next?

What’s Next?

Dan’s accomplishments are even more impressive considering some of the challenges that he has overcome. In 2018, he wrote an inspiring piece about the challenges that come with dyslexia.

As he mentions in the piece, he managed to hide his dyslexia by working tirelessly, including by essentially memorizing all of his seminars and lectures. The stress that he put on himself may have contributed to his first open-heart surgery in 2001. After stepping down as BTI President to relieve some of the pressure in 2004, he continued to enjoy doing science more than ever.

While Dan is retiring from full-time research, he expects to maintain a regular presence around the Institute as an Emeritus Professor. “Three open-heart surgeries and six bouts of pneumonia, and I’m still kicking,” he says.

Schroeder suspects that Dan will always remain involved in science, and that the two will continue to have enlightening conversations and publish papers together.

“I think BTI can count on Dan’s continued support and presence at seminars, asking questions and sharing his ideas and vision for the future of BTI,” says Schroeder.

While Dan’s accomplishments can be measured far beyond publications and awards, those numbers are impressive. He has published 215 research papers, and 37 book chapters and reviews. His many awards and honors include the Marshall Scholar to the United Kingdom (1971-1973), Searle Scholar (1982-1985), McKnight Scholar (1983-1986), Faculty Research Award from American Cancer Society (1984-1988), Japan Society for Promotion of Science Fellow (1997), Fellow of the American Academy of Microbiology (2001), Noel T. Keen Award for Research Excellence in Molecular Plant Pathology (2011), and Fellow of the American Association for Advancement of Science (2012).