News

Pear genomes show evidence of independent domestication in Asia and Europe

Thousands of pear cultivars exist across the world. Credit: Ryan McGrady

Esteemed by ancient empires and modern times alike, pears are one of the most beloved and among the oldest of cultivated fruits. More than 25 million tons of pears are produced annually across the globe, including thousands of cultivars, and dozens of wild species can be found throughout Asian and European forests.

The story of the pear (Pyrus) began 65 to 55 million years ago, when the earliest Pyruslineage appeared in the mountainous regions of southwestern China. Pyrus dispersed eastward and westward, which led to the divergence of two very different pears: Asian and European pears.

Researchers from the Boyce Thompson Institute (BTI) and partnering institutions in China, the U.S., and New Zealand, report their findings on the domestication of the pear in Genome Biology.

“European pears have pear-shaped fruits with soft and smooth flesh, few stone cells, along with strong aroma and flavor, while Asian pears bear round-shaped fruits with crisp flesh, high sugar content, low acid content, minimal aroma, and mild flavor,” said Zhangjun Fei, associate professor at BTI and co-author of the paper.

Little is known about the evolutionary history of pears and how Asian and European pears came to be so distinct. To answer this question, the researchers sequenced 113 wild and cultivated pear accessions from worldwide collections.

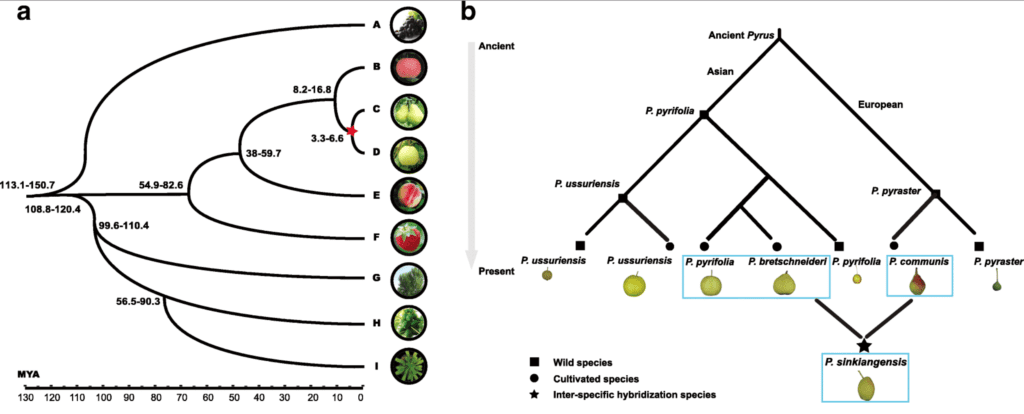

Genetic relationships and divergence times of pear species. a Genetic relationships of wild and cultivated pear species. b Divergence time of Asian and European pears. A, Vitis vinifera; B, Malus × domestica; C, Pyrus communis; D, Pyrus bretschneideri; E, Prunus persica; F, Fragaria vesca; G, Populus trichocarpa; H, Carica papaya; and I, Arabidopsis thaliana.

They then used phylogenetic and population genomics analyses to explore relationships among the various cultivated and wild pear accessions. These comparisons allowed them to identify genomic regions affected by artificial selection during the domestication history of Asian and European pears.

The researchers propose a model that after their origination in southwest China and distribution to Europe, Asian and European pears underwent independent domestications, resulting in pear fruits with different texture, flavor and shape.

“Population structure analysis provided new evidence to support the admixed genetic background of some pear species,” the authors add, “which was likely driven by self-incompatibility.” This self-incompatibility, which prevents plants from self-fertilizing, promoted outcrossing and accounts for the pear’s extensive genetic diversity.

In addition to these findings, this study offers an unprecedentedly large amount of pear genomic data that can be used in breeding efforts. “The high-density genome variation data generated under this study provides a fascinating platform for breeders to improve speed and accuracy of ‘marker-assisted selection’ in pear,” said Fei.

“The genomic regions and candidate genes affected by human selection and related to certain agronomical traits discovered here will provide valuable information to guide future pear research and improvement.”

Subscribe to BTI's LabNotes Newsletter!

Contact:

Boyce Thompson Institute

533 Tower Rd.

Ithaca, NY 14853

607.254.1234

contact@btiscience.org

Copyright © 2023 | Boyce Thompson Institute | All rights reserved | Privacy Policy | Cookie Policy