News

Genetic changes in tomatoes may help crops produce early and often

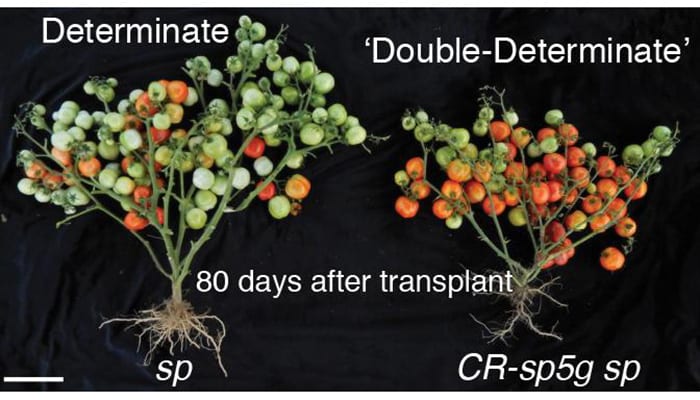

Improving on a much-loved variety of cherry tomato (left), the team used gene editing to get ripe fruit two weeks earlier (right).(Image courtesy of Lippman lab/CHSL)

Home gardeners in the U.S. and Europe can thank early tomato growers, who selected plants that ignore seasonal changes in day length, for enabling their backyard bounty.

Wild plants have evolved to consider the lengthening and shortening of days when deciding the right time to flower, but the domestication process has changed that connection in many crops, as humans began cultivating the plants away from their original locations. A new study in Nature Genetics by researchers at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) and the Boyce Thompson Institute (BTI) identified genetic variations that make tomato plants “day neutral.” These plants flower without regard for the length of the day, so they can be cultivated far from their native soil—near the equator in South America. Using gene editing technology, the researchers demonstrated that they could rapidly create a quick-flowering tomato plant by altering one of the genes. Similar changes in other crops could expand the geographic range of these crops, or stimulate an earlier yield.

The wild relatives of tomato first became domesticated in the Andean regions of South America, where anecdotal evidence suggests that they likely evolved to grow during long, sunny days, and to begin flowering and yielding fruit as the days got shorter. Around the 16th Century, when people brought tomatoes to the Mediterranean Basin and even farther north, the plants had to adapt to the shorter days of a northern summer.

To find the genes underlying this shift, researchers in the lab of Associate Professor Zachary Lippman at CSHL, compared the genomes of early- and late-flowering plants belonging to a species of furry, seed-filled wild tomato called S. galapagense. They identified relevant regions that mapped to a gene for a known flowering hormone, called florigen, and a gene called SELF-PRUNING 5G (SP5G), whose activity suppresses flower production.

The researchers think that naturally existing mutations in the SP5G gene that affect how and when a tomato plant responds to day length, is what initially enabled people to create day-neutral tomato varieties that fruit at higher latitudes.

To confirm the role of SP5G, BTI Assistant Professor Joyce Van Eck used the gene editing technology CRISPR/Cas9 to create mutations in SP5G. The resulting tomato had a compact “determinate” shape and quickly produced flowers, leading to earlier tomato production.

“By targeting those genes with CRISPR, we were able to show changes [in flowering time] when the expression was disrupted,” said Van Eck.

Gene editing allowed them to condense the selection process that humans used hundreds of years ago to produce day neutral tomatoes, so that it occurred within a single generation. “By manipulating those components that regulate when a plant flowers, you can broaden where those crops can be grown,” said Van Eck.

Other factors, such as temperature and moisture, also affect where crops will thrive, so gardeners in the Northeast won’t be growing mangoes outside anytime soon.

But the study shows that editing these genes could be a rapid approach for developing new, early yield varieties that can be fine-tuned for productivity at specific latitudes. Additionally, altering SP5G could be one of the first steps in engineering the domestication of a wild species for agricultural use.