History

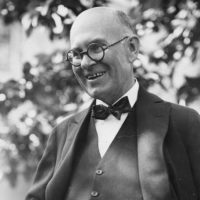

The Colonel

William Boyce Thompson (1869–1930) was a rare combination of hardheaded realist and dreamer. He was schooled in the rough mining towns of Montana and at Phillips Exeter Academy mining stocks on Wall Street and owning and operating mines. He was not only a shrewd man of business but also had great intellectual curiosity, particularly about science. He wished to be a force for good in the world and supported various philanthropies. Thompson’s life is chronicled in his 1935 biography The Magnate. He visited Russia in 1917, just after the overthrow of the monarchy, when civil war was raging and starvation was rampant. Thompson was a member of an American Red Cross relief mission that was present during the political unrest after the abdication of the czar, the interim government of Kerensky, and rise of Lenin and Trotsky. He was awarded the honorary title of colonel by the American Red Cross. The mission saw firsthand the suffering of the people and the inability of the social democratic government headed by Alexander Kerensky to feed the hungry. Although Thompson added more than $1 million of his own to the relief funds provided by the U.S. government, he was unable to convince President Woodrow Wilson to do more. Soon after the Americans had returned home, the Kerensky government fell and the Bolsheviks came to power. Thompson’s hopes for a prosperous democracy in Russia were ended. The Russian experience convinced him that agriculture, food supply, and social justice are linked. World political stability in the future, he prophesied, would depend on the availability of adequate food. This conviction, along with his faith in science, helped to shape his next philanthropic project.

William Boyce Thompson (1869–1930) was a rare combination of hardheaded realist and dreamer. He was schooled in the rough mining towns of Montana and at Phillips Exeter Academy mining stocks on Wall Street and owning and operating mines. He was not only a shrewd man of business but also had great intellectual curiosity, particularly about science. He wished to be a force for good in the world and supported various philanthropies. Thompson’s life is chronicled in his 1935 biography The Magnate. He visited Russia in 1917, just after the overthrow of the monarchy, when civil war was raging and starvation was rampant. Thompson was a member of an American Red Cross relief mission that was present during the political unrest after the abdication of the czar, the interim government of Kerensky, and rise of Lenin and Trotsky. He was awarded the honorary title of colonel by the American Red Cross. The mission saw firsthand the suffering of the people and the inability of the social democratic government headed by Alexander Kerensky to feed the hungry. Although Thompson added more than $1 million of his own to the relief funds provided by the U.S. government, he was unable to convince President Woodrow Wilson to do more. Soon after the Americans had returned home, the Kerensky government fell and the Bolsheviks came to power. Thompson’s hopes for a prosperous democracy in Russia were ended. The Russian experience convinced him that agriculture, food supply, and social justice are linked. World political stability in the future, he prophesied, would depend on the availability of adequate food. This conviction, along with his faith in science, helped to shape his next philanthropic project.  In 1920 he decided to establish an institute for plant research. Its purpose would be to study “why and how plants grow, why they languish or thrive, how their diseases may be conquered, how their development may be stimulated by the regulation of the elements which contribute to their life.” The study of plants, he hoped, would result in practical, substantial contributions to human welfare. The growing population of the United States would need a larger food supply. The study of plant diseases and the development of cures for them; the creation through genetic research of hardier, more nutritious, disease-resistant crop plants and more viable seeds; the study of insects that damage food crops; and the production of new pesticides all would contribute to this goal. Conservation would be another goal: “Men were too prone in America to destroy vegetation, especially forests and grazing surfaces,” he said. “They must learn now to conserve.” The effect of industrial pollutants on plants and the development of methods to protect plants would be studied. Thompson expected the institute to make valuable contributions to general scientific knowledge, biology, and medicine.

In 1920 he decided to establish an institute for plant research. Its purpose would be to study “why and how plants grow, why they languish or thrive, how their diseases may be conquered, how their development may be stimulated by the regulation of the elements which contribute to their life.” The study of plants, he hoped, would result in practical, substantial contributions to human welfare. The growing population of the United States would need a larger food supply. The study of plant diseases and the development of cures for them; the creation through genetic research of hardier, more nutritious, disease-resistant crop plants and more viable seeds; the study of insects that damage food crops; and the production of new pesticides all would contribute to this goal. Conservation would be another goal: “Men were too prone in America to destroy vegetation, especially forests and grazing surfaces,” he said. “They must learn now to conserve.” The effect of industrial pollutants on plants and the development of methods to protect plants would be studied. Thompson expected the institute to make valuable contributions to general scientific knowledge, biology, and medicine.

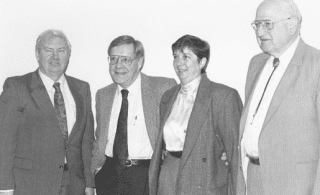

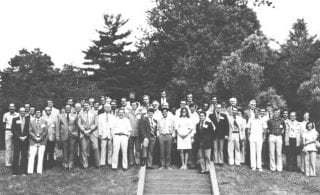

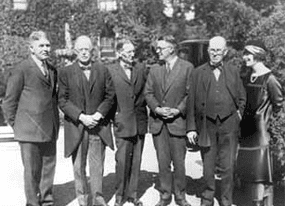

Some members and directors attending BTI opening ceremonies, September 24, 1924. (From left to right) Dr. William Crocker, Dr. John M. Coulter, Dr. L. R. Jones, Dr. R. F. Bacon, Col. William B. Thompson, and Mrs. Theodore Schulze.

William B. Thompson endowed the institute with $10 million, a veritable fortune in the 1920s. He hoped that this “seed” money would enable the institute to acquire the very best scientists, equipment, and supplies and then to develop relationships with industry and the government to help finance research. The licensing of institute patents with companies has helped balance funding during years of lean government support. Thompson believed that commerce and industry are beneficial to society and that commercial development of research results would spread the institute’s discoveries.

Laying the Foundation

By 1924 an interdisciplinary team of academic researchers had been assembled, and the facilities were finished. Many luminaries attended the dedication ceremonies on September 24 for the Boyce Thompson Institute for Plant Research (named not for Thompson himself, but for his parents Anne Boyce Thompson and William Thompson).

Dr. William Crocker

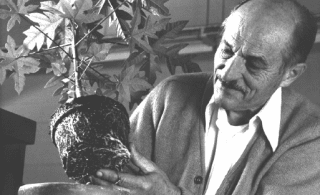

William Crocker, an associate professor of plant physiology at the University of Chicago, became the institute’s first managing director. He, Thompson, and other academic advisers spent several years planning the institute. Herbert H. Whetzel of Cornell urged Thompson to build the institute at a university so it could cooperate with university research programs, but Thompson wanted to be personally involved, and the institute was built across the street from his mansion in Yonkers, New York.

Early History

From 1924 to 1932, Louis O. Kunkel studied the yellows diseases of plants about which neither the causative agent nor the method of transmission was known but that could destroy crops, orchards, and ornamental plants. Kunkel discovered that yellows disease in asters, which he thought was caused by a virus, was transmitted by leafhoppers. (Many years later it was discovered that the infectious agent was a phytoplasma.) To assist him in his work on the phases of the yellows and virus disease problems, he assembled a team of young scientists. Among them were Francis O. Holmes and Helen Purdy Beale. Beale conducted pioneering studies of plant viruses and, over many years, compiled and edited the Bibliography of Plant Viruses and Index to Research, published in 1976, well after her retirement in 1952. Holmes devised the “local lesion” assay, which identifies certain virus infections in plants, and discovered that plant varieties differ greatly in their susceptibility to various virus strains. By crossing the plants, he made the significant finding that resistance to a virus is inherited and linked to a single gene. Lela V. Barton studied seed storage and viability and became a prominent seed physiologist. For more than forty years she compiled information for her Bibliography of Seeds, published in 1967. Frank E. Denny, a plant physiologist from 1924 to 1950, headed a project on overcoming bud dormancy in potato. He was assisted by Lawrence P. Miller, a plant biochemist at the institute from 1929 to 1966. Miller was the first institute scientist to receive a government grant from the Atomic Energy Commission (now the Department of Energy) that resulted in the first use of radionuclides at the institute. In 1960 a National Science Foundation program was established to enable selected high school teachers to spend eight weeks working in a laboratory at the institute. In 1962, a similar program composed of third-year high school honor students was established. Miller directed both programs for several years. After his retirement he edited the three-volume series Phytochemistry, published in 1973.

From 1924 to 1932, Louis O. Kunkel studied the yellows diseases of plants about which neither the causative agent nor the method of transmission was known but that could destroy crops, orchards, and ornamental plants. Kunkel discovered that yellows disease in asters, which he thought was caused by a virus, was transmitted by leafhoppers. (Many years later it was discovered that the infectious agent was a phytoplasma.) To assist him in his work on the phases of the yellows and virus disease problems, he assembled a team of young scientists. Among them were Francis O. Holmes and Helen Purdy Beale. Beale conducted pioneering studies of plant viruses and, over many years, compiled and edited the Bibliography of Plant Viruses and Index to Research, published in 1976, well after her retirement in 1952. Holmes devised the “local lesion” assay, which identifies certain virus infections in plants, and discovered that plant varieties differ greatly in their susceptibility to various virus strains. By crossing the plants, he made the significant finding that resistance to a virus is inherited and linked to a single gene. Lela V. Barton studied seed storage and viability and became a prominent seed physiologist. For more than forty years she compiled information for her Bibliography of Seeds, published in 1967. Frank E. Denny, a plant physiologist from 1924 to 1950, headed a project on overcoming bud dormancy in potato. He was assisted by Lawrence P. Miller, a plant biochemist at the institute from 1929 to 1966. Miller was the first institute scientist to receive a government grant from the Atomic Energy Commission (now the Department of Energy) that resulted in the first use of radionuclides at the institute. In 1960 a National Science Foundation program was established to enable selected high school teachers to spend eight weeks working in a laboratory at the institute. In 1962, a similar program composed of third-year high school honor students was established. Miller directed both programs for several years. After his retirement he edited the three-volume series Phytochemistry, published in 1973.  Percy W. Zimmerman and Alfred E. Hitchcock joined the institute in the late 1920s and conducted research on plant growth regulation. They realized that halogenated aryloxyacetic compounds must play a role in regulating plant growth. The synthesis of 2,4-D and the discovery of its hormonal activity were significant advances in the understanding of plant growth that led to the development of rooting hormones and hormone-based weedkillers that kill weeds but not grass. Credit for the discovery of 2,4-D’s hormonal action is variously ascribed to (among others) Zimmerman and Hitchcock, DuPont researchers, a British team, and a gifted teenager, J. Carleton Gajdusek, who later won the Nobel Prize. No doubt with some supervision, Gajdusek synthesized 2,4-D during his summer job in a BTI laboratory. Zimmerman and Hitchcock published the first report of the hormonal activity of 2,4-D. They were also pioneers in studying the effects of air pollution on plants. Both of them won many scientific awards for their achievements. S. E. A. McCallan won recognition for his research on fungicides and air pollutants. He participated on the team that studied fungicidal action and effects of the pollutants sulfur dioxide and hydrogen sulfide on plants and microorganisms. He served as secretary and president of the American Phytopathological Society and received the society’s Award of Merit. In 1975, he authored A Personalized History of Boyce Thompson Institute, which covers the period from 1924 through 1974. McCallan served as corporate secretary from 1959 to 1973 and was affiliated with the institute for fifty-two years, from 1929 to 1981. 1923_2002 lists articles published by BTI scientists beginning with William Crocker in 1923.

Percy W. Zimmerman and Alfred E. Hitchcock joined the institute in the late 1920s and conducted research on plant growth regulation. They realized that halogenated aryloxyacetic compounds must play a role in regulating plant growth. The synthesis of 2,4-D and the discovery of its hormonal activity were significant advances in the understanding of plant growth that led to the development of rooting hormones and hormone-based weedkillers that kill weeds but not grass. Credit for the discovery of 2,4-D’s hormonal action is variously ascribed to (among others) Zimmerman and Hitchcock, DuPont researchers, a British team, and a gifted teenager, J. Carleton Gajdusek, who later won the Nobel Prize. No doubt with some supervision, Gajdusek synthesized 2,4-D during his summer job in a BTI laboratory. Zimmerman and Hitchcock published the first report of the hormonal activity of 2,4-D. They were also pioneers in studying the effects of air pollution on plants. Both of them won many scientific awards for their achievements. S. E. A. McCallan won recognition for his research on fungicides and air pollutants. He participated on the team that studied fungicidal action and effects of the pollutants sulfur dioxide and hydrogen sulfide on plants and microorganisms. He served as secretary and president of the American Phytopathological Society and received the society’s Award of Merit. In 1975, he authored A Personalized History of Boyce Thompson Institute, which covers the period from 1924 through 1974. McCallan served as corporate secretary from 1959 to 1973 and was affiliated with the institute for fifty-two years, from 1929 to 1981. 1923_2002 lists articles published by BTI scientists beginning with William Crocker in 1923.

50s and 60s

George L. McNew became the second managing director in 1949, when Crocker retired. A plant pathologist, McNew did distinguished research concerning the chemical processes responsible for disease in plants. He was an able administrator who improved salaries and pensions at the institute, hired young researchers to join the aging staff, purchased modern equipment, and for the first time actively sought government (rather than just industrial) sponsorship for research. Leonard H. Weinstein, Jay S. Jacobson, Delbert C. McCune, David C. MacLean, Richard H. Mandl, and, later, John A. Laurence carried on the air pollution research begun by Crocker, Zimmerman, and Hitchcock. In the 1960s they undertook a very large program in this field that is still ongoing. Their research has encompassed many areas, including the effects of pollutants on the biochemistry, physiology, growth, and yield of plants and the development of air-monitoring methods and air-quality standards for numerous state agencies in the United States and several foreign countries. In 1978, Weinstein was recognized for his many years of leadership by being nominated as the institute’s first named scientist, the William B. Thompson Scientist. For more than two decades he directed research on the effects of fluoride on plants that was the foundation for the development of the largest scientific group dedicated to studying the effects of air pollution on crops and trees in the nation and perhaps the world. He continues to help industries comply with air-quality standards around the world. Weinstein served on the institute’s Board of Directors from 1973 to 1997, when he became an emeritus director. By 1967 the pollution of the Hudson River had become of great concern to conservationists. Edward H. Buckley, a researcher in Hudson River ecology for more than twenty years, was the project leader of the institute’s Estuarine Study Group, which compiled information on the biological status of the river and published it in 1977 in An Atlas of the Biologic Resources of the Hudson Estuary. Samuel S. Ristich and David L. Sirois were staff scientists on the project. This publication, edited by Weinstein, became an international resource on estuarine systems.

George L. McNew became the second managing director in 1949, when Crocker retired. A plant pathologist, McNew did distinguished research concerning the chemical processes responsible for disease in plants. He was an able administrator who improved salaries and pensions at the institute, hired young researchers to join the aging staff, purchased modern equipment, and for the first time actively sought government (rather than just industrial) sponsorship for research. Leonard H. Weinstein, Jay S. Jacobson, Delbert C. McCune, David C. MacLean, Richard H. Mandl, and, later, John A. Laurence carried on the air pollution research begun by Crocker, Zimmerman, and Hitchcock. In the 1960s they undertook a very large program in this field that is still ongoing. Their research has encompassed many areas, including the effects of pollutants on the biochemistry, physiology, growth, and yield of plants and the development of air-monitoring methods and air-quality standards for numerous state agencies in the United States and several foreign countries. In 1978, Weinstein was recognized for his many years of leadership by being nominated as the institute’s first named scientist, the William B. Thompson Scientist. For more than two decades he directed research on the effects of fluoride on plants that was the foundation for the development of the largest scientific group dedicated to studying the effects of air pollution on crops and trees in the nation and perhaps the world. He continues to help industries comply with air-quality standards around the world. Weinstein served on the institute’s Board of Directors from 1973 to 1997, when he became an emeritus director. By 1967 the pollution of the Hudson River had become of great concern to conservationists. Edward H. Buckley, a researcher in Hudson River ecology for more than twenty years, was the project leader of the institute’s Estuarine Study Group, which compiled information on the biological status of the river and published it in 1977 in An Atlas of the Biologic Resources of the Hudson Estuary. Samuel S. Ristich and David L. Sirois were staff scientists on the project. This publication, edited by Weinstein, became an international resource on estuarine systems.  Richard C. Staples joined the institute in 1952. He did pioneering work on the mechanisms that induce rust fungi to infect the leaves of host plants. He was part of an earlier team that described the first self-inhibitors of germination in rust spores. He later demonstrated that many but not all rust fungi can sense and respond precisely to the ridges of the stomatal guard cells through which they enter their hosts. During his career, Staples received the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation’s Senior U.S. Scientist Award and the Ruth Allen Award of the American Phytopathological Society (APS) and was elected a Fellow of the APS. In 1987 he was named the George L. McNew Scientist. He retired in 1991 and continues collaborative research with scientists at the New York State Agricultural Experiment Station. Zohara Yaniv came to BTI in 1967 to work with Staples as a postdoctoral research fellow. To gain a better understanding of the mechanism of obligate parasitism, Yaniv and Staples studied the ribosomal activities in uredospores of the bean rust fungus and their role in spore germination and senescence. For ten summers, Yaniv worked as an instructor—and later the director—in BTI’s NSF Student Science Training Program. She left the institute in 1978 when it moved to Ithaca. Projects to find ways to control bark beetles that were killing pine trees in western and southern forests were begun. To support this work, the institute acquired acreage in Grass Valley, California, and Beaumont, Texas. Jean Pierre Vité joined the staff in 1957 to direct research at the Grass Valley Forestry Laboratory. Beginning in 1963, Vité also directed the Beaumont Forest Laboratory. J. Alan Renwick and Patrick R. Hughes, then graduate students, joined Vité’s team. Together they discovered that male and female beetles (depending on the species) give off pheromones, chemicals that attract beetles of the other sex. The researchers used this knowledge to develop a form of nontoxic control that was produced commercially and is still in use. Renwick continued his work in chemical ecology, and his research in taste modification in crop-eating insects may lead to control measures that will protect crops by changing insects’ food preferences. Hughes studied insect viruses with a view to developing a nontoxic pesticide that will kill crop-eating insects. In the course of his work, he has developed an efficient, inexpensive system for rearing insect larvae at high density that may be of value in pharmaceutical production. Karl Maramorosch joined BTI in 1961. He is internationally known for his research in the transmission of plant viruses and mycoplasma-like agents by insects. In addition, he was an early pioneer in invertebrate cell culture. He won many awards, including the Wolf Prize for Agriculture in Israel, edited many volumes, and fostered many young scientists. In 1998, at the age of eighty-one, he received an Honoree Award from the Society for Invertebrate Pathology in Sapporo, Japan. Robert R. Granados, the Charles E. Palm Scientist, started at the institute in 1964. He was influenced to come to BTI by the research of Louis Kunkel and Karl Maramorosch. Granados established novel insect cell-culture lines that are in common use for recombinant protein production worldwide. He made important contributions to our knowledge of insect viruses and the molecular biology of the insect midgut. This work involved identifying new gene products for use in developing insect-tolerant transgenic plants. Jun Mitsuhashi and Eishiro Shikata did outstanding work in the 1960s. Mitsuhashi collaborated with Maramorosch in research in tissue cultures of insect carriers of plant diseases. Shikata became well known for his early research on pea enation mosaic, a disease of pea plants, and for his studies of plant viruses and their insect vectors, especially those associated with plant wound tumors.

Richard C. Staples joined the institute in 1952. He did pioneering work on the mechanisms that induce rust fungi to infect the leaves of host plants. He was part of an earlier team that described the first self-inhibitors of germination in rust spores. He later demonstrated that many but not all rust fungi can sense and respond precisely to the ridges of the stomatal guard cells through which they enter their hosts. During his career, Staples received the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation’s Senior U.S. Scientist Award and the Ruth Allen Award of the American Phytopathological Society (APS) and was elected a Fellow of the APS. In 1987 he was named the George L. McNew Scientist. He retired in 1991 and continues collaborative research with scientists at the New York State Agricultural Experiment Station. Zohara Yaniv came to BTI in 1967 to work with Staples as a postdoctoral research fellow. To gain a better understanding of the mechanism of obligate parasitism, Yaniv and Staples studied the ribosomal activities in uredospores of the bean rust fungus and their role in spore germination and senescence. For ten summers, Yaniv worked as an instructor—and later the director—in BTI’s NSF Student Science Training Program. She left the institute in 1978 when it moved to Ithaca. Projects to find ways to control bark beetles that were killing pine trees in western and southern forests were begun. To support this work, the institute acquired acreage in Grass Valley, California, and Beaumont, Texas. Jean Pierre Vité joined the staff in 1957 to direct research at the Grass Valley Forestry Laboratory. Beginning in 1963, Vité also directed the Beaumont Forest Laboratory. J. Alan Renwick and Patrick R. Hughes, then graduate students, joined Vité’s team. Together they discovered that male and female beetles (depending on the species) give off pheromones, chemicals that attract beetles of the other sex. The researchers used this knowledge to develop a form of nontoxic control that was produced commercially and is still in use. Renwick continued his work in chemical ecology, and his research in taste modification in crop-eating insects may lead to control measures that will protect crops by changing insects’ food preferences. Hughes studied insect viruses with a view to developing a nontoxic pesticide that will kill crop-eating insects. In the course of his work, he has developed an efficient, inexpensive system for rearing insect larvae at high density that may be of value in pharmaceutical production. Karl Maramorosch joined BTI in 1961. He is internationally known for his research in the transmission of plant viruses and mycoplasma-like agents by insects. In addition, he was an early pioneer in invertebrate cell culture. He won many awards, including the Wolf Prize for Agriculture in Israel, edited many volumes, and fostered many young scientists. In 1998, at the age of eighty-one, he received an Honoree Award from the Society for Invertebrate Pathology in Sapporo, Japan. Robert R. Granados, the Charles E. Palm Scientist, started at the institute in 1964. He was influenced to come to BTI by the research of Louis Kunkel and Karl Maramorosch. Granados established novel insect cell-culture lines that are in common use for recombinant protein production worldwide. He made important contributions to our knowledge of insect viruses and the molecular biology of the insect midgut. This work involved identifying new gene products for use in developing insect-tolerant transgenic plants. Jun Mitsuhashi and Eishiro Shikata did outstanding work in the 1960s. Mitsuhashi collaborated with Maramorosch in research in tissue cultures of insect carriers of plant diseases. Shikata became well known for his early research on pea enation mosaic, a disease of pea plants, and for his studies of plant viruses and their insect vectors, especially those associated with plant wound tumors.  Donald W. Roberts joined the institute in the 1960s. Roberts’s research on fungal diseases of insects worldwide included establishing new insect pathology teams in Brazil and the Philippines. In 1980 Roberts organized the Insect Pathology Resource Center, which included scientists from the USDA, Cornell, the New York State Agricultural Experiment Station, and the institute. The center supported training for national and international scientists, maintained a repository of insect pathogens, and performed basic and applied research. In 1996 Roberts became the Roy A. Young Scientist. Also in the 1960s, H. Alan Wood began his research on the physical and biological properties of plant and fungal viruses and then moved into the area of insect virology. His research has played an important role in the study of the basic biology and molecular genetics of insect viruses and in the designing and field testing of insect virus pesticides. On August 9, 1989, in Geneva, New York, he conducted the first field release in the United States of a genetically engineered virus. In the 1990s Wood researched methods to optimize the production of pharmaceutical proteins with insect viruses and to define the attachment of sugars to proteins by insects. Vlado Macko joined the staff in 1969. He and his colleagues discovered the chemical nature of host-specific toxins including victorin, HS toxin, and peritoxin. The work on plant disease models in which toxins play a central role led to the discovery of protectants and latent toxins and to the finding of victorin binding protein and its location in mitochondria and guard cells. He also characterized the chemical nature of self-inhibitors of spore germination in plant pathogenic fungi. Macko received the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation’s Senior U.S. Scientist Award. Dewayne C. Torgeson began his professional career at the institute in 1952 as a plant pathologist, working on an industrial project related to discovery and development of pesticides. Torgeson served as program director of the Bioregulant Chemicals Program from 1963 to 1985, as corporate secretary from 1973 to 1991, and as a member of the Board of Directors from 1978 to 1996, when he became an emeritus director.

Donald W. Roberts joined the institute in the 1960s. Roberts’s research on fungal diseases of insects worldwide included establishing new insect pathology teams in Brazil and the Philippines. In 1980 Roberts organized the Insect Pathology Resource Center, which included scientists from the USDA, Cornell, the New York State Agricultural Experiment Station, and the institute. The center supported training for national and international scientists, maintained a repository of insect pathogens, and performed basic and applied research. In 1996 Roberts became the Roy A. Young Scientist. Also in the 1960s, H. Alan Wood began his research on the physical and biological properties of plant and fungal viruses and then moved into the area of insect virology. His research has played an important role in the study of the basic biology and molecular genetics of insect viruses and in the designing and field testing of insect virus pesticides. On August 9, 1989, in Geneva, New York, he conducted the first field release in the United States of a genetically engineered virus. In the 1990s Wood researched methods to optimize the production of pharmaceutical proteins with insect viruses and to define the attachment of sugars to proteins by insects. Vlado Macko joined the staff in 1969. He and his colleagues discovered the chemical nature of host-specific toxins including victorin, HS toxin, and peritoxin. The work on plant disease models in which toxins play a central role led to the discovery of protectants and latent toxins and to the finding of victorin binding protein and its location in mitochondria and guard cells. He also characterized the chemical nature of self-inhibitors of spore germination in plant pathogenic fungi. Macko received the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation’s Senior U.S. Scientist Award. Dewayne C. Torgeson began his professional career at the institute in 1952 as a plant pathologist, working on an industrial project related to discovery and development of pesticides. Torgeson served as program director of the Bioregulant Chemicals Program from 1963 to 1985, as corporate secretary from 1973 to 1991, and as a member of the Board of Directors from 1978 to 1996, when he became an emeritus director.

1974 to 1980

Emeritus scientists Leonard H. Weinstein and Richard C. Staples wrote a firsthand account of the Boyce Thompson Institute (BTI) spanning a quarter century. This retrospective covers the move to Cornell and the people who contributed to the affiliation between Cornell and BTI. This colorful, “unofficial” account also covers breakthrough research from BTI’s recent history.

Preface

Originally, this period in BTI’s history was to be written by Dewayne C. Torgeson, scientist, Program Director, and Corporate Secretary. It was interrupted by his untimely death, and we were asked to take over the task in 2003. Other longtime colleagues were lost during this same period: Richard H. Mandl, environmental scientist, Dorothy Reddington, Director of Development, and Colleen Sloan, Secretary and Administrative Assistant for the Environmental Biology Program. We dedicate this history to them. If this continuation of the McCallan history (“A Personalized History of Boyce Thompson Institute,” which covered the years from dedication in 1924 to 1974) is not written in the traditional manner, it is because the actual events that make up a history always have degrees of humor, irony, and cynicism, as well as points of view. We wish to thank especially, Valleri Longcoy and Elizabeth Estabrook, who have been creatively helpful and collegial. This should not diminish the value of the willing help also provided by John Dentes; a critical review of a draft of the text by Alan Renwick and Bob Kohut; and other helpful support from Brian Gollands and Carl Leopold. Len Weinstein Dick Staples Boyce Thompson Institute May 1, 2005 This history is dedicated in their memory with appreciation for their important contributions to the BTI.

Clockwise from top left: Colleen Sloan, Richard Mandl, Dewayne Torgeson and Dorothy Reddington

Introduction

Colonel William Boyce Thompson 1869–1930

In 1917, immediately prior to the Communist revolution, Colonel William Boyce Thompson, a wealthy mining entrepreneur, visited Russia as part of a twenty-person mission appointed by the American Red Cross. It was one of President Wilson’s initiatives to bring peace to that region of the world. There, Colonel Thompson saw at firsthand the abject poverty and starvation of Russian peasants, and he became convinced that Russia might be stabilized if the production of food and fiber could be improved. In 1924, following the model of New York City’s Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, Colonel Thompson founded and endowed the Boyce Thompson Institute for Plant Research with the objective “to study why and how plants grow, why they languish or thrive, how their diseases may be conquered, and how their development may be stimulated.” Although endowed from its inception, the breadth and scope of its research activities would not have been possible without outside support from individuals, foundations, and government agencies. In 1975, S. E. A. McCallan wrote “A Personalized History of Boyce Thompson Institute,” which included the institute’s history from its founding on September 24, 1924 to the period when we planned the move from Yonkers to Ithaca. In 2003, the authors were asked to continue the history of BTI from 1974 onward. We chose to cover the period up to 2000, leaving the period beginning in the twenty-first century to a future “historian.” There have been many changes in the institute during its “rebirth” on the Cornell University campus. One of these changes is the fewer number of women staff scientists (now called faculty). In the first fifty years, there were twenty-eight women scientists listed by McCallan as senior scientists, and even as early as 1924, at its founding, there were nine women scientists listed on the staff. In 2000, there were also nine women listed, two of whom were senior staff, the other seven research associates. From 1975 through 2000, there has been only one tenure-track woman, but she was not given tenure and left the institute. A number of women scientists had distinguished careers. Among the early senior staff, one must list Irene Dobroscky, a virologist who was at the institute in 1924. She studied the transmission of plant viruses (some of which are known now to be phytoplasmas) by insects in L. O. Kunkel’s laboratory, where each scientist worked independently. Helen Purdy (Beale) was also a virologist responsible for the precipitin reaction, and she published Bibliography of Plant Viruses and Index to Research. Lela Barton was a preeminent seed physiologist and was responsible for giving us Bibliography of Seeds and Seeds: Their Preservation and Longevity, among many other contributions. Norma Pfeiffer was an eminent taxonomist, classifying a number of plant families on the basis of megaspore characteristics. Sophia Eckerson was an accomplished plant pathologist and virologist. These are only a few of the women who contributed to the institute’s reputation in the early days of BTI. One hopes for a more realistic distribution of faculty in the future. Since 1975, there has been a strong emphasis by the institute on molecular genetics leading to a reduction or elimination of other disciplines. By the end of 2000, it appeared that programs for which the institute has been renowned in the past would be eliminated, in part because funding had become difficult to obtain for the more “traditional” sciences. Today, its research program has become adapted to the stimulating environment at Cornell, where it continues to change and take advantage of the sophisticated technology becoming available during the twenty-first century.

The End of an Era

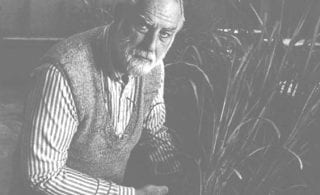

Dr. George McNew

From his appointment on September 1, 1949 until his retirement on May 31, 1974, George L. McNew devoted all his energies to making BTI a leader in the plant sciences, developing strong programs in entomology, plant pathology (including virology), and environmental biology. At the same time, perhaps not consciously, he molded an institution that was tightly knit and had a family aura. It is difficult to describe this feeling of “family.” Dr. McNew, and his wife Elizabeth, took a great interest in the institute employees, from the maintenance workers to the scientific staff, although some people felt that this interest was excessive and overly paternal. The McNews showed their interest in several ways. They entertained often at their beautiful home overlooking the Hudson River. Both Dr. George McNew and Mrs. McNew were concerned with the employees’ welfare. In a financial emergency, it was not unusual for Dr. McNew to make a personal loan or, in a health emergency, both of them were known to pitch in with necessary housekeeping and cooking. On May 6, 1974, the Annual Meeting of the BTI Board was convened at the Hilton Inn in Tarrytown, New York, where the affiliation agreement with Cornell University was approved. This was followed by a reception in Dr. McNew’s honor, attended by board members, senior staff, and their wives. No managing director before or since McNew has dedicated so much time and energy to the administration of BTI or demonstrated such extreme concern for the scientific staff and other personnel. At the same board meeting, Dr. Richard H. Wellman was appointed to assume the position of managing director as of June 1, 1974. Wellman had close ties to BTI. He was hired by S. E. A. McCallan, after receiving his PhD from Washington State University, as a plant pathology fellow in a new Carbide and Carbon (later Union Carbide) project. Wellman was head of the project until 1954, when he left for the New York office, where he eventually became general manager of the Chemicals and Plastics Group of Union Carbide. He joined the Institute Research Advisory Committee in 1968 and was elected to the Board of Directors in 1969.

The Move to Cornell

The desire that the institute be associated with a university actually traces back to its founding, when William Boyce Thompson had his vision of creating an institution that he hoped would be to plant science what the Rockefeller Institute was to human and animal science. As a start, he asked advice from a number of prominent scientists. Among them was H. H. Whetzel, a professor of plant pathology at Cornell University, who suggested that this new institute be located in association with a university, preferably Cornell, but Thompson, although aware of the advantages of a university affiliation, had already decided it would be built across the street from his mansion, “Alder,” where he could observe its construction and operation. Little did he know that Whetzel’s proposal would someday become a reality. Further details of the institute’s founding years are described in S. E. A. McCallan’s A Personalized History of Boyce Thompson Institute (1975). In the 1950s, mild rumblings were heard from Dr. McNew and other staff members (which for convenience only, we shall hereafter refer to as “faculty”). At that time, both biological sciences and BTI were making great strides, and there was a greater realization that BTI was isolated from other research and academic institutions. Although there were a few graduate students from Columbia, Rutgers, Fordham, and Cornell universities who pursued their thesis research projects at the institute, there was no day-to-day interaction with colleagues from other institutions with whom ideas could be shared, discussed, developed, and modified, or collaborative studies could be carried out. Attendances at an occasional meeting was not sufficiently fulfilling, and talk of moving BTI to a college or university became a frequent subject among the faculty and administration. Indeed, the increased urbanization surrounding the institute, pollution from motor vehicles, and home heating (actually an advantage for the Environmental Biology program which stressed the effects of air pollution on plant life!) were becoming a serious problem. It was very difficult to modernize the building (because it was so well constructed that any change was exceedingly costly). But it also became clear among the administration that we would eventually have to seek another home.

Aerial View of The Boyce Thompson Institute Building and Grounds in Yonkers, New York. The property extended from the homes to the right of the photo, along the trees at the top, to the home visible on the left.

Despite occasional flirtations with moving, the first actual step in its relocation was offered in 1973 by Dr. Roy Young, a former graduate student of Dr. McNew’s and Vice President for Research at Oregon State University (OSU). Dr. Young began discussions with McNew and members of the BTI Board, and he interested OSU’s President McVicar, the Oregon governor, Tom McCall, and members of the Oregon state legislature. They were sufficiently interested that a bill was passed providing a sum of $6,750,000 to build and equip a headquarters for the institute on the OSU campus, and a formal invitation was sent to BTI’s Chairman of the Board, William T. Smith. The Executive Committee traveled to Oregon where they were feted for a couple of days and met with important university and state officials. Smith took a straw poll of the board members, which turned out to be very favorable to a move to OSU and he initialed a Memorandum of Agreement on May 15, 1973. This was confirmed in a letter from Dr. McNew to Roy Young of May 17, 1973, but McNew’s bias toward Cornell and his use of mild pressure in the negotiations became evident:

After we completed the visit to the Campus (OSU), I believe every member of our group was ready to accept Oregon as a future home for BTI provided there were firm assurances that the building would be provided and a suitable formal contract could be developed to implement the brief Memorandum of Understanding [actually it was a Memorandum of Agreement] upon that afternoon in Corvallis. Of course, there were two of us who felt that Cornell certainly had an advantage in general prestige and financial support for the project but we would not have insisted in exploring these possibilities further if we had a firm plan at Oregon State. The key people were definitely enthusiastic over what they saw in Corvallis and were ready to firm up an agreement along the lines of the Memorandum of Understanding as soon as the Board of Directors had approved the basic concept.

When the early negotiations with OSU became public, New York’s lieutenant governor, Malcolm Wilson, a native of Yonkers, moved to keep the institute in New York State, and along with Chancellor Boyer of SUNY, convinced Governor Rockefeller to bring a bill before a special session of the legislature in July that would provide a “biological laboratory, greenhouse facilities” on the Cornell campus. The bill was passed in the Senate, but encountered difficulties in the Assembly because some from Ithaca and some from the Yonkers area did not know what it was all about or did not want the institute to leave Yonkers. There were also allegations in the State Assembly that BTI was running an “exclusive and racist country club” in Stanfordville for BTI employees. What they were actually referring to was a 400+-acre farm that had been acquired for experimental purposes. At the behest of Dr. S. E. A. McCallan and others, a 1.3-acre pond was constructed and a cottage was built using volunteer employee labor. This cottage was designated for use by researchers and other employees for weekends or even week-long vacations following a specific set of rules and guidelines. It was hardly a country club, and certainly wasn’t racist; but it was a place where employees could go for short stays or drive up for the day, and it was the site of the BTI Annual Picnic, an extremely well-attended event that featured a great deal of eating, swimming, volleyball, softball, horseshoes, fishing, and other activities. At any rate, the allegations were somehow defused and the bill was passed under the able leadership of Assemblywoman Constance Cook. Following the invitations from both OSU and Cornell, there was a flurry of activity. Visits to OSU and Cornell were made by Secretary McCallan and the Executive Committee, and by Alva App, Dewayne Torgeson, and Leonard Weinstein representing the program directors. Reports were made by all visitors to the Board of Directors. The positive sentiment on the board to accept the OSU offer did not translate to the faculty, a great majority of whom favored Cornell. When examined dispassionately, Cornell appeared to be the superior choice. Some faculty, including Leonard Weinstein, decided that if OSU were chosen, they would not make the move. In Weinstein’s case, this had less to do with geographical than family reasons (aging parents and in-laws). The tip-off that BTI was favoring a Cornell affiliation became obvious in a letter from Dr. McNew to Miles Romney, the Vice Chancellor of the Oregon State System of Higher Education on July 30, 1973:

In all honesty, I should advise you that Governor Rockefeller introduced a bill into the special session of the New York State legislature on Wednesday afternoon, July 25, upon recommendation of the State University of New York, proposing Cornell University be provided with $8,500,000 to build and furnish facilities for Boyce Thompson Institute. . . . My latest advice is that the Senate passed the bill 54-5 but it is hung up in the Assembly by our local representatives who do not want us to leave Yonkers. . . . At the moment, Cornell expects the bill to pass but I have no data one way or the other.

And, as late as August 28, 1973, the Vice Chancellor of the Oregon State System of Higher Education requested that the president of that organization approve a change in the affiliation agreement with OSU. To make matters cloudier, after approval by the New York state legislature, the BTI Board reversed its earlier animus toward Cornell and voted 16-0 to accept its offer and move the institute to the Cornell campus. Dr. McNew, a man of many words, and in a voice that sounds a bit neo-Victorian, discussed the decision in a letter to Dr. Young dated September 14, 1973. This mea culpa is given in its entirety:

As Dr. Wellman has advised you, the general sentiment at our Board meeting on September 12 was to see if a satisfactory contract could be developed with Cornell that would gain the approval of the SUNY Board. The set of very definitive principles developed in negotiations between Dr. Wellman and Dr. Palm [Dean of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Cornell] and approved by officials at Cornell was sufficiently attractive to warrant their reduction to legal language, something which could not be done adequately earlier in the compressed time schedule imposed upon us. It is impossible to predict what obstructions and frustrations will be encountered in this process, but I concur with the Board that it had to be done before a final decision could be made. I was surprised to find that strong sentiment prevailed not to sign a provisional agreement with Oregon State while we were seriously negotiating with Cornell. Two members strongly objected to the morality and possibly the legality of entering into such an arrangement in poor faith and the others concurred in spite of Dr. Wellman’s and my explanation of your and President McVicar’s viewpoint. I sincerely hope this has not caused you any embarrassment because of the Emergency Board moving its session up before our meeting date. The growing sentiment for Cornell, as I see it, come from many considerations. The primary factor, of course, is that at long last they have a definite proposal with money to back it up to implement their suggestions to me of last October and their proposal of last December to the Board. Our Board was deeply impressed that they willingly modified their stand for complete consolidation to affiliation of two coordinated agencies on campus and even went so far as to seek status of BTI as an absolutely independent entity in its own facility provided by the State. The administration at the College of Agriculture had actually proposed to the State Department of Commerce and later to the State University that they build and assign the building to BTI without formal affiliation with the College, but this could not be legally done with State funds. Of course, Cornell had $8.5 million or $1.75 million more than you for construction of facilities. This position of strength did not overwhelm us; but they were in the process of accepting from the contractors on August 22 a veterinary research tower of 160,000 square feet constructed at a cost of $8.4 million. We could see exactly what could be obtained from their appropriation in constructing and equipping two thirds as much space for BTI with appended greenhouses. With all due respect to your fine facilities in the Bioscience building, their veterinary creation was out of this world in architectural design, tailored usefulness for various purposes, versatility and capabilities of modification, so it could be essentially as good 50 years from now as today. If any one thing swung some of us over to their column, it was this facility which included a remarkable array of furnishings and equipment as part of the construction cost. There were many supporting items such as a site where our greenhouses and labs could be attached directly, a mass of surrounding research activities within 100 yards in veterinary microbiology, plant pathology, entomology, soils and nutrition and bioclimatic facilities (which we can use gratis when desired), 24-hour service for our environmental installations, convenience to the Mann Library, a free shuttle bus service operating on a 15-minute schedule from our front door to all points on campus and ready access to large nearby parking lots. Convenience to business contacts was most favorable with two flights in each direction from the Ithaca airport (10 minutes from the proposed laboratory site) to New York City (53 minutes), Cleveland (1-1/2 hours), Pittsburgh (1 hour), Washington (1-1/2 hours) and Chicago (2-1/2 hours) [Ah, for the good old days!!] with major nationwide flights from Syracuse airport (70 minutes) and Elmira airport (95 minutes). Conferences in these cities could be held 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. without overnight delay. The staff preferences for Cornell undoubtedly had a strong bearing with Program Directors, Senior Scientists, Research Associates and Post-doctoral Fellows presenting an almost completely united front to the Board. While several [referring to a few faculty scientists and Board Members] would have liked to see us in Oregon for personal reasons, they seemed to feel the weight and strength of Cornell could not be denied as benefiting BTI. You should know and take pride in the reaction of everyone at BTI toward OSU as it was presented to us. Our Executive Committee and the visiting Program Directors were no less impressed than Dick Wellman and myself. The evidence of dynamic growth and progressiveness everywhere on campus was tremendous. The quality and scope of facilities and the dedication of your staff were evident everywhere. I believe that the warmth and friendliness of your administration, deans and scientists will live in our minds and hearts forever. No one should ever interpret the reverses on our Board as derogatory to OSU or the energy, skill and dedication with which you, Dean Krause and President McVicar presented your invitation and followed up in presenting your case. Our Board feels that we were presented with two generous and appealing alternatives from two of the most meritorious institutions in our field of science. It is almost a flip of the coin as to which should receive preference because one is fully established and progressing constructively while the other is excitingly dynamic and alive with possibilities for the future. Had we not been a foundation incorporated in New York State, had the State political structure not shown such determination to retain us in this State or had Cornell and the State University of New York not been so perceptive in analyzing the worries and needs of our Board, there is no question but that we would have signed the agreement with OSU last Wednesday and probably broken off negotiations with Cornell. I need not dwell on my personal frustrations during the past five months. Regardless of my personal desires and the warmth of our personal relations, I had to be guided entirely by what I believe to be to the best interests of Boyce Thompson Institute. If I had done less, I would not be worthy of the trust bestowed upon me by the BTI Board or the mutual respect and friendship which prevail between the two of us. Dick and I have debated item by item the considerations that have come before us step by step. While not agreeing in all personal appraisals, we have agreed decisively that we should be guided by what we see to be the most practical in achieving the best posture possible for BTI and its long range future and that personal considerations had to be ignored insofar as possible. I pray you will understand it has not been easy for either of us.

A Decision Is Made

Once the decision was made to move to Cornell, a building committee was formed, consisting of Donald Melhop, Chairman, Richard Lankow, Richard Mandl, Alan Wood and S. E. A. McCallan. Albany selected the architects, Ulrich Franzen and Associates. The building, exclusive of the greenhouse, was to be 63,132 square feet, somewhat larger than the building in Yonkers. The move to Cornell was scheduled for 1974, but New York State’s lagging economy postponed building construction, and we all wondered when, and if, we would ever make the move. Dave Cutting, a local businessman, community leader, and president of the Tompkins County Area Development Committee, was told by Arthur H. “Pete” Peterson, the Cornell treasurer, at a Citizen Savings Bank Board meeting that BTI was not coming to Cornell after all and, because of the state’s financial problems, had decided to go to Oregon. This rumor had only a passing relationship to the truth. What happened was that there were members of the board who felt strongly that Cornell had reneged on its promise and that we should renegotiate with OSU. When Cutting heard the news from Peterson, he went to see Raymond van Houtte, president of the County Trust Company bank and a community leader. They immediately flew to New York City, apparently under terrible weather conditions (so extreme that they weren’t confident that they would survive another day) to speak with the chairman of the New York State Dormitory Board, to whom they asked the question: If we can raise the money for the building, will you issue the construction bonds? Receiving a positive answer, they obtained pledges for $9.4 million, $0.9 million more than required. Cornell University faculty and staff pledged $1.5 million, local banks $3.5 million, regional banks $2.4 million, and BTI $2 million. In the final tally, the construction bonds were oversubscribed, and BTI was let off the hook and not required to invest any of its endowment funds. The bonds were to pay an interest rate of 9 percent but, when issued, paid 8 percent and ended up being called by the state in two years, much to the disappointment of the bond holders. In preparation for the move, members of the Building Committee, administrators, program directors, other scientists, and key maintenance personnel made numerous trips to Cornell to attend meetings of various kinds; present talks to Cornell faculty, staff, and students about BTI, its history, and goals for the future; and look for housing, check school quality, neighborhoods, and so forth. Dewayne Torgeson especially made trips to negotiate details of the Affiliation Agreement (see Appendix IX). Donald Mehlhop and Richard Mandl were the two most involved with the building’s construction and attended many meetings with the architects and building contractors and subcontractors until the building was completed. As an aside, Don Mehlhop had been a submarine commander in World War II and was an experienced leader of men (actually, he and his submarine sat at the bottom of Tokyo harbor when Japan surrendered). Dick Mandl was a faculty member in the Environmental Biology Program who had remarkable natural talents for instrument design and construction basics. Mandl took primary responsibility in making certain that the plant growth facility and scientific needs were suitable. They made a strong team (although accompanied by occasional loud disagreements) that helped to develop a building that was not only beautiful and award winning, but also functional, and that met, and continues to meet, the needs of the staff. Scientists who made the move to Cornell were allowed to select and design their offices and laboratories. Years later, renovations were made because of changes in equipment and style of furnishings, as new scientists arrived.

A New Home in Ithaca

Building construction started in 1977 and, by October 1978, nearly the entire scientific staff, many technicians, the building superintendent, and the head of the maintenance department began moving from Yonkers into the new building. A Yonkers mover, the 7 Santini Brothers, was contracted to move all of us who chose to relocate in Ithaca. There were few restrictions on what and how much we could move. Some people even moved dozens of clay pots and lumber. For a few years after the move, 7 Santini Brothers boxes were as common in the new building as cockroaches were in the old one. Occasionally one still runs onto 7 Santini Brothers boxes around the institute and in many basements and attics. Upon Colonel Thompson’s death, the institute was left a number of paintings from the Thompson estate and most, if not all, of them could be found hanging in the building—in administrative offices, the library, the entrance foyer, and a number of scientists’ offices. Just prior to the move to Ithaca, Park Bernet, a New York auction house, catalogued and made cost estimates of the paintings for auction. Len Weinstein was fond of a small still life (signed “Hurst”) in his office in an ornate gold frame. The appraiser valued it at $300. Weinstein would have been allowed to buy it at that price, but he decided that $300 was too much money for such a small painting. Later, it fetched $8,000 at auction, a foretelling of Weinstein’s future financial dealings (divestments).

The Current Boyce Thompson Building

During trips before the move and after our arrival, the Cornell community warmly welcomed us. Somehow, though, Cornell personnel, realtors, and the Ithaca community as a whole had the impression that we were being paid outrageously high salaries. In fact, before the move, realtors often arrived in Yonkers with photographs of homes available for purchase, invariably mansions and accompanied by, “We understand this is the kind of home Institute people will be looking for.” This, of course, was light years from the truth. One of the photographs shown to Weinstein was of the mansion that is now Cornell President Lehman’s home. After being revived, Weinstein said that he didn’t want to heat more than fifteen rooms. As it turned out, the institute raised most salaries to conform generally to Cornell’s pay scale. This may have been due partly to the wording regarding comparability in the affiliation agreement with Cornell (see appendices). The first few months after the move were heady indeed. The excitement of being affiliated with a university, let alone a great one, was exhilarating. The Environmental Biology Program was especially welcomed because of its reputation as one of the best and largest air pollution groups in the United States, and because there was no equivalent group at Cornell. Their experimental farm of twelve acres, just adjacent to Route 366, was set up and ready for the summer following the move. Many BTI scientists were also invited to become adjunct professors of various departments, among which were Plant Pathology, Natural Resources, and Plant Biology. No one was invited to join Ecology and Evolutionary Biology or Entomology. There were very few sour notes associated with the move, but those that did present themselves were based on the exaggerated salary story and complaints that SUNY turned over to us outsiders, a beautiful building to occupy while so many other building at the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences were old and substandard. This was true. The dedication ceremony for the new building was held on April 24, 1979, in the Law Auditorium at the School of Veterinary Medicine. At the time of the dedication, BTI’s research was concentrated in five areas: biological nitrogen fixation, biological control of insects, air pollution effects on agriculture and forestry, plant stress, and the development of bioregulant chemicals. On April 25–26, 1979, there was a Dedication Symposium, “Linking Basic Research to Crop Improvement Programs in Less Developed Countries,” cosponsored by Cornell University and partially supported by the Ford Foundation. The program stated that it was “A celebration of affiliation with the N.Y. State College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Cornell University.” Richard Staples organized and chaired the symposium, and the subjects were clearly selected to be a template for the “new” directions of BTI under its new Managing Director, Richard Wellman. It did not take long before we noticed a discernible change in BTI’s reputation as Cornell’s incandescent standing began to rub off on us. This is still true today. As McCallan (1975) stated in his history of BTI:

Mr. Searls, a rugged individual of the old school, was to become something of a stormy petrel who was not satisfied with the status quo at the Institute and wanted to shake things up for the better.

Fred Searls, who liked to list himself as “Mining Engineer, 14 Wall Street, New York City” worked for Colonel Thompson in mining explorations around the world and eventually became president of Newmont Mining Corp., the organization founded by William Boyce Thompson. Searls often told stories about “fighting off bandits” during mineral explorations in China, which, when told in full, would undoubtedly be far more interesting than this history. At McCallan’s second BTI annual meeting as a director (in 1947):

he [Searls] called the attention of the Directors to the ravages of beetles and other insects to pine and other timber in the Northwest and desired to know whether the Institute could save the situation. Dr. Crocker (then Managing Director) did not take kindly to Searls’ suggestion and replied “that the U.S. Government was already spending huge sums for this purpose” . . . Word filtered down to the staff that the new Member wanted the whole Institute to work on “reforesting the Rocky Mountains”. Thus at this point, Fred Searls became in the eyes of the staff something of a villain on the Board. Little did we think that in 1953 he would become Chairman of the Board.

As Chairman of the Board, Searls was persistent in pushing the institute toward a bark beetle program. He also pressured the institute into other things. For example, he prodded the institute into investigating, for his friend Bernard Baruch, the value of cellular therapy, a cult medical treatment to ensure perpetual youth begun in 1930 by a Swiss physician, Paul Niehans. Earlier, Niehans had been involved in the infamous transplantation of monkey glands for a similar purpose. “Graduates” of the cellular therapy program included Konrad Adenauer, Pope Pius XII, Gloria Swanson, and many other notables. (Winston Churchill applied but was turned down because of his inveterate cigar smoking and drinking.) Assigned by McNew to the “investigation” were Walter Tulecke and Leonard Weinstein. Although little was accomplished, they attended several meetings in New York City of a cellular therapy group, met many “interesting” people (including Wolfgang Goetze-Clarens, a disciple of Niehans’s, who was fawned over outrageously all that evening). The New York Times the next day published a list of foreign doctors, including Goetze-Clarens who were caught falsifying their medical exams. (Some youth doctor!) It was not all a complete waste because Tulecke and Weinstein ended up having Thanksgiving dinner in South Carolina with Searls, Baruch, and Baruch’s “nurse” (who was called “Navarro”) not on the traditional Thursday but on the previous Tuesday! Details of the Weinstein/Tulecke escapade are not germane to this document, but they could be considered adventures in the occult. As we departed for the airport, Baruch gave each of us a bag of persimmons. It was Weinstein’s first (and last) persimmon and his only Thanksgiving dinner with Bernard Baruch! Fortunately, the story of BTI’s involvement with the founding youth doctor, Paul Niehans, and how BTI was able to extricate itself from being further entangled in this activity, is a long story, but the “youth” doctors are still in business.

The Stanfordville Farm

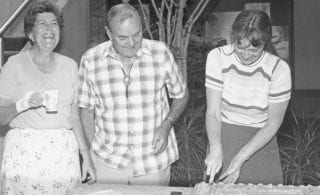

Annual picnic at Dutchess county farm. Left to right: Jane Beardo, Joan DeFato, Jill (Goldman) Mancini.

Although we were far from being a “forestry institute,” Dr. Clyde Chandler had been carrying on a breeding program on larch at the institute arboretum, located about a mile from the main building. But in 1956, when the New York State Thruway Authority condemned and purchased 52 acres of its best land, which included the nursery area, the arboretum was doomed. BTI sold the remaining land for what seemed to be a pittance, after which it changed hands several times, each sale at a progressively higher price. This may have been a portent of future institute land dealings. The area condemned by New York State is now the Yonkers toll booth area of the New York State Thruway. The remaining property eventually became a Westchester County park. In order to continue the larch breeding program, and perhaps for other reasons, the institute acquired a 441.5-acre farm in Stanfordville, Dutchess County, New York in 1959. Dr. Chandler’s larch seedlings were transplanted to a 17-acre parcel on the farm. By diverting a stream and creative use of a bulldozer, a small lake of 1.3 acres was formed. A cottage was built, ostensibly for the use of researchers, although the lake and cottage became an employee benefit and the site of the annual institute picnic. Jerry Way, who supervised activities at the Yonkers arboretum, moved to a house nearby and took over everyday management of the farm. Later, when the New York State legislature was debating a bill for funds to construct the building at Cornell for our use, the farm was used to accuse BTI of running an exclusive and private “country club.” With the impending move to Cornell, the property was sold in December 1975 and March 1976 for a total of $297,000. Contrary to most past and future BTI land dealings, there was a net profit to the institute of $193,800!!

The BTI Home Campus and Lenoir

At the Annual Meeting of Members of BTI on May 12, 1975, the move to Cornell appeared to be more and more imminent and the members spent most of their time discussing the divestment of land: properties in Beaumont, Texas; Grass Valley, California; Stanfordville, New York, and the institute’s home campus, which now comprised a parcel of about 130 acres, including the Hudson River Country Club (which surrounded the institute’s original campus of 7 acres on three sides), and was formerly restricted (which meant no Jews, blacks, Latinos, and few Catholics) and Lenoir, an estate of 16 acres across North Broadway from the institute and immediately north and adjacent to the beautiful Thompson estate, Alder. Lenoir and the Hudson River Country Club were acquired when Dr. Orrin Wightman (who became the heir to the estate and country club through marriage) died and the institute exercised its right of first refusal as had been agreed upon at an earlier date. The original acquisition of the property seemed essential to the institute’s future at that time, but it became a liability when the real estate market turned sour and we had to pay taxes to the City of Yonkers for all but a 40-acre parcel that was incorporated as an experimental farm and part of the main campus. There were many suitors who wanted to continue the golf course and country club, start a new university, or build a shopping center, each of which failed because they were not financially sound, far beyond our capabilities, or vigorously opposed by neighbors. (Even today, there is a move to tear down the original institute building and replace it with modern medical offices, a health club, and, allegedly, a Dunkin’ Donuts shop). Naturally, there is also an opposition group that wanted the building to be declared a historic landmark home. The building will not be demolished, but will not become a historic landmark. In the meantime, the U.S. economy went into a steep decline and there were few serious customers for the land. Also, the city of Yonkers had changed the zoning of the property to Industrial Park, which more than doubled the taxes. With the initial investment in the land of $2,960,000, taxes for several years, and loss of interest on the capital, the institute became desperate to find a buyer. It was finally agreed to sell the property to the Robert Martin Corporation, developers of executive parks. At the May 12, 1975 meeting, the members authorized the Executive Committee to conduct negotiations to sell the property for a price that most members and directors felt was too low, but had to be accepted because time was short and there were no other prospects. At the Executive Committee meeting of June 19, 1975, recognizing the poor condition of the real estate market and the somewhat awkward location of the property, the committee voted nearly unanimously to sell the property (without the Lenoir estate) for $2,300,000. Dr. McNew cast a negative vote stating that the price was much too low and that we should continue to seek out purchasers. As an aside, one of us (LW) was a close friend of the attorney for Robert Martin. He rarely spoke of anything associated with his legal activities, but because of our friendship he told me that the institute lawyer, claiming that he was too busy to write the contract, asked him, the Robert Martin lawyer, to write it, a monumental error in this kind of negotiation. After that, the lawyer friend said, it was like “taking candy from a baby.” The Lenoir property (a mansion and 16 acres of land overlooking the Hudson River) was sold to the County of Westchester in 1977 for $504,000. These negotiations were not the last in the institute’s policy of divesting land at a large real or potential capital loss. In this case, considering the original cost of acquiring the country club and Lenoir, the selling price, taxes on much of the property for eight years and the lost interest from capital, a conservative estimate of the loss to the institute’s endowment was about $8,000,000.

The Beaumont, Texas, Laboratory

Bark beetles were raising havoc with longleaf and loblolly pines in the South and the institute was asked by the Southern Forest Research Institute (a consortium of several lumber companies) to establish a laboratory on 390 acres of low-lying land west of Beaumont near the village of Sour Lake. Patrick Hughes, a remarkably versatile entomologist, who retired from BTI in 2003, and Alan Renwick, an outstanding chemical ecologist, were resident or part-time scientists there, with Jean Pierre Vité, who came to BTI from Göttingen, Germany, as the overall director. Vité was a brilliant and dynamic entomologist. The group found, among other discoveries, that the pheromones, frontalin, trans-verbenol, and verbenone were produced by three species of Dendroctonus bark beetles and that synthetic samples of these compounds were useful in concentrating the beetle attacks for exercising control measures. As McCallan (1975) said, the Southern Forest Research Institute “decided to dissolve and withdraw their support in September of 1974. Presumably they felt that the major goals had been accomplished and they were not about to support long-range basic research especially when the U.S. Forest Service was funding such.” The BTI land and holdings were sold, and the sole resident scientist, Patrick Hughes, was transferred to Grass Valley. According to contemporary sources, the land was sold for a price far below its market value.

The Grass Valley Laboratory

BTI Bark-beetle laboratory building at Grass Valley, California

As mentioned earlier, Fred Searls Jr., the Chairman of the boards of Newmont Mining and of BTI was insistent that something be done about the damage being caused to forests and shade trees by various species of bark beetles; the estimated damage being about five times that caused by forest fires. Because it was felt that a basic study of bark beetles and forest trees could not be accomplished in greenhouse and laboratory studies, Mr. Searls proposed that the North Star Gold Mine property, a tract of 660 acres south of Grass Valley, California, be given to the institute for future studies. This was augmented by a gift of 20 acres and a house by Mr. James D. Hague, and the purchase of two adjoining tracts lying along the southern boundary, giving a total of 740 acres for research. Funding also came from the Margaret T. Biddle Foundation (Margaret Biddle was the only Thompson child) and the institute endowment. Title to the property was acquired in December 1957. The director of the laboratory (as well as the one in Beaumont, Texas) was again Jean Pierre Vité. Alan Renwick worked both there and at Beaumont, Texas with Vité. Patrick Hughes also worked there after being transferred from Beaumont. The forest consisted mainly of ponderosa pines with some black oaks, the only broadleaf species. A summary of the research carried out and their trials and tribulations has been summarized earlier (McCallan, 1975). A decision was made to move the activities of the Grass Valley operation to OSU. In 1977, the Grass Valley property was under contract to Robinson Enterprises for $840,000. Several board directors and scientists who had worked there protested this price. BTI had been receiving about $100,000 per year in timber sales and another $100,000 per year in sales of rock from the earlier mining activities, but the protests were to no avail and the land was sold. This was another “feather” in BTI’s land-dealing misadventures. Despite the fact that there was no financial loss, because the land and buildings had been donated to the institute, there was a loss in what could have been received for the property.

The Nepera Park Farm

From its early days until it was sold, the institute’s farming activities took place at the 25-acre Nepera Park Farm, located east of the Hudson River Country Club boundary. The farm had been used extensively by Percy W. Zimmerman and A. E. Hitchcock during the period when they were actively studying rooting and other plant hormones. It was also used for field testing of pesticides and other miscellaneous activities. But its greatest use was by the Environmental Biology Program for studying the effects of air pollutants on plant growth, yield, and quality. After the institute acquired the Hudson River Country Club property, the farm activities were moved from Nepera Park to a somewhat larger tract behind the institute building. The Nepera Park Farm was then sold to the Gestetner Corporation. They, in turn, sold the property to the Wilmorite Corporation, a large real estate development company. Wilmorite, apparently feeling a downturn in the economy and not seeing an immediate use for the property sold it to Consumer’s Union for a headquarters building. Thus began a saga that led to a lawsuit against the institute and culminated in a settlement never made public. The story began when Consumer’s Union, in considering the purchase of the property from Wilmorite, insisted that it must be a pristine, uncontaminated parcel. Wilmorite contracted with an environmental consulting firm to take soil samples for wide-spectrum analysis. Traces of chlordane were found in several cores, particularly in one. Concerned that they might lose the sale, Wilmorite had the areas where chlordane was found excavated and sent the potentially contaminated soil to a special incinerator where anything organic would be decomposed. Wilmorite then asserted that the problem was caused by BTI and filed suit for reimbursement of costs of more than $3 million. Dr. Ralph Hardy was the president of the institute at the time, and he was energized by this claim because of its potentially negative impact on the institute’s endowment. BTI retained a law firm in Albany (Whiteman, Osterman & Hannah, LLP) that specialized in environmentally related litigation. Our insurance company initially asserted that coverage did not exist and, at this point, the records of further actions have been blurred intentionally. Even as a board member, Leonard Weinstein was not informed of the actions. The denouement was that our insurance company paid a significant portion of the costs, but BTI was responsible for an amount that probably reached seven figures.

The Richard Wellman Years (1974–1980)

Richard H. Wellman, Former Managing Director